The first phase of Lunar exporation was Program E1, a series of missions to explore deep space and impact the Moon. Satellites had discovered properties of near Earth orbit, most noteably the radiation belts. The E1 probes would measure cosmic radiation, plasma and micrometeorites well beyond the influence of the Earth's magnetic field. They would also measure the distant magnetic field of the Earth and try to detect the Moon's field, if it had one.

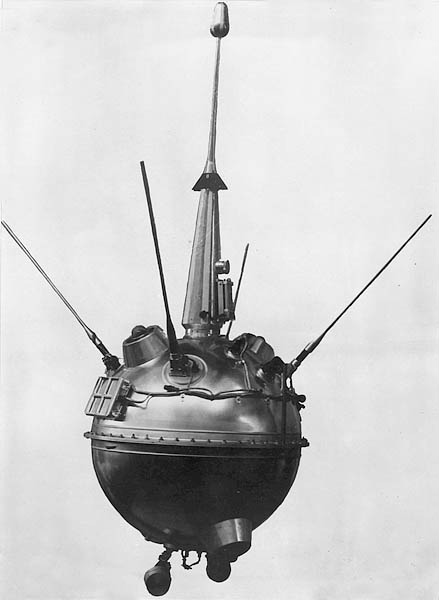

The Scientific Pod

Soviet Pennants for Luna-2 The pod also contained commemorative pennants, to be delivered to the Lunar surface. These included a metal ribbon bearing the date and the name of the USSR, and a pair of stainless steel spheres (7.5 and 12 cm in diameter) made up of pentagonal medals with the Soviet coat of arms. The spheres were filled with liquid and an explosive charge to burst apart on impact and scatter the pennants. However, with a Lunar impact speed of 3.3 km/sec, it is questionable if any part of the spacecraft could survive without being vaporized. Launches of Luna-1 and Luna-2

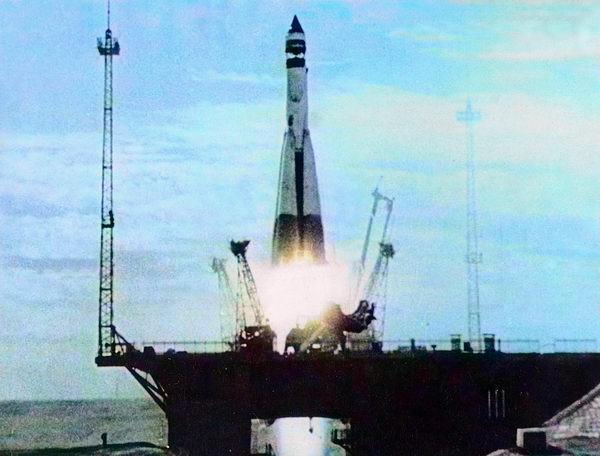

Luna Rocket Launch After less than a year of rapid development, the first launch was attempted on September 23rd, 1958. The first stage of the rocket failed after 87 seconds, due to combustion instability, and a second attempt on October 12th ended in the same way after 104 seconds. The problem was traced to a resonant vibration of 9 to 13 Hz in the fuel lines. After correcting this problem with fuel line dampers, a third launch took place on December 4th. This time the rocket failed after 245 seconds due a defect in the hydrogen peroxide pump of the engine. Concerns about the reliability of the RTS-12B telemetry system led to the installation of a redundant radio system called Jupiter-1, designed by Evgeny Gubenko. RTS-12B sent 120 measurements in a two-minute cycle using pulse-time modulation (PTM). Jupiter sent the same information as RTS-12B, on 19.993 MHz using pulse-duration modulation (PDM). An extensible ribbon antenna was added to the scientific pod, on the opposite end from the magnetometer mast. Jupiter was first used on the third Luna launch attempt. At 16:41:21 GMT on January 2 1959, a launch was almost completely successful and the "First Soviet Cosmic Rocket" became the first spacecraft to achieve escape velocity. A few years later, the mission was retroactively referred to as "Luna-1". The Luna-1 rocket should have been able to hit a target on the Moon within 100-200 km, but an error in the ground-based guidance system caused Block-E to burn a few seconds too long, and it missed the Moon by 6000 km after 34 hours of flight and entered into a heliocentric orbit. The trajectory error was caused by a 2-degree error in presetting the R-7 radio guidance system. Radio communication was maintained for 62 hours, to a distance of 597,000 km. The RTS-12B telemetry system had failed, but the 183.6 MHz ranging system still functioned, and scientific telemetry was sent by the Jupiter-1 shortwave system. A fifth launch attempt made on June 18 failed.

The Trajectory of Luna-2 At 06:39:42 GMT on September 12, the Second Cosmic Rocket was successfully launched. Engine cut-off occured at 6:51:45, at which point it was on an escape trajectory that would intersect the Moon. Based on results from Luna-1, some changes and additions to scientific instrumenation were made. Luna-2 carried out its mission successfully and impacted the Moon near the region of Palus Putredinus at about 30° N, 0°W. Impact of the scientific pod occured at 21:02:24 GMT on September 13, followed by the impact of Block-E about 30 minutes later. Tracking the Impact of Luna-2

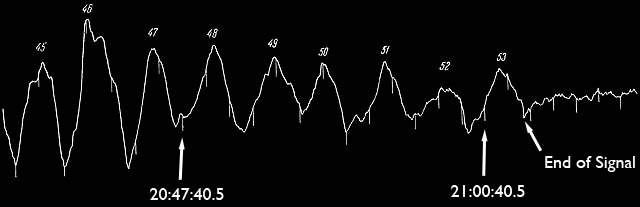

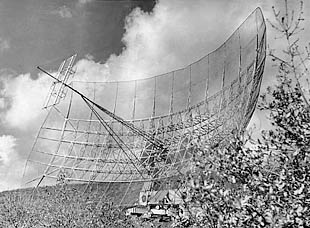

Boguslavsky's long-distance tracking system on Mount Koshka measured the range and radial velocity of the scientific pod. Nearby, radio astronomers from the Lebedev Institute of Physics erected two parabolic antennas to measure the probe's angle of direction by radio interferometry. The antennas had an aperture of about 200 square meters and were calibrated against several known sources, such as the radio galaxy in Cygnus A. The distance between the focal points was thus determined to great accuracy (175.896 meters), before the interferometer was aimed at the 183.6 MHz signal from the Luna-2 scientific pod.

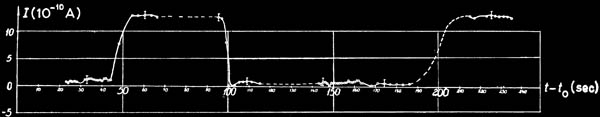

Interferometer Signal from Luna-2 As the pod's angle crossed the lobes of constructive interference between the antennas, its signal was amplified, then diminished as it passed through a zone of destructive interference. Each peak represented a change in angle of 31.9 arc minutes. The moment of signal loss was noted at lobe 53.43, giving an angular measurement accurate to about one arc minute.

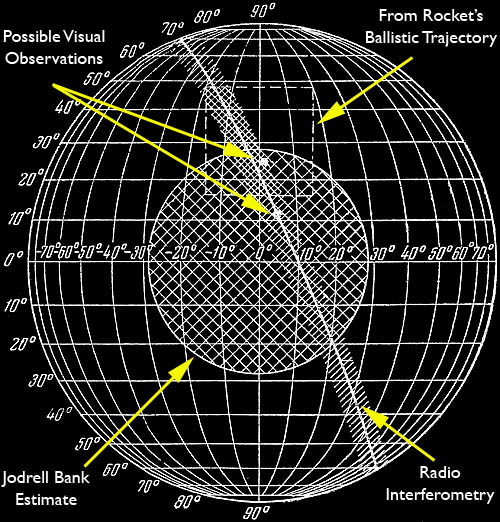

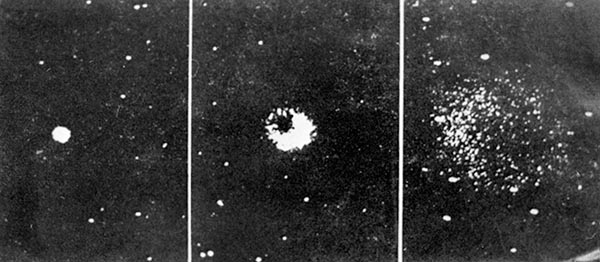

Locating the Impact of Luna-2 on the Moon's Face The position of Luna-2's impact was estimated from several measurements. In England, the Jodrell Bank Radio Observatory had the world's largest steerable parabolic antenna at that time, and the Russians sent them tracking and frequency information. From the probe's acceleration, they were able to calculate that it struck somewhere within 7 arc minutes of the center of the Moon's face. The rectangular region indicated above represents the impact calculated from the rocket's initial course, as measured by the radio guidance system. It demonstrates a remarkably accurate trajectory, for that time. The radio interferometry system measured only one angular dimension, placing the impact point within one arc minute of a line. The estimated time and location of the impact was announced ahead of time, and so a number of astronomers looked for the impact by telescope. With a final speed of 3 km/sec, the scientific pod had enough kinetic energy to generate about 300,000 calories, raising its temperature to as high as 4500 K and ejecting dust. It is a matter of some debate whether this could have been observed from Earth. In all, seven sightings were published, but many have been discounted. The English astronomer Patrick Moore, using a 12.5 inch relfector, observed a pinpoint of light at about 21:02:23 near the schneckenberg mountains, 11.2° N 4.97°E. This flash was observed at the same time and spot by another English astronomer, H. Percy Wilkins, using a 15 inch reflector. Wilkins also reported seeing a small dark ring following the flash. At the Konkoly Observatory in Hungary, a dark expanding dust cloud was observed at the moment of impact, at the coordinates 25.7° N 4.97° E. Scientific Experiments and Results

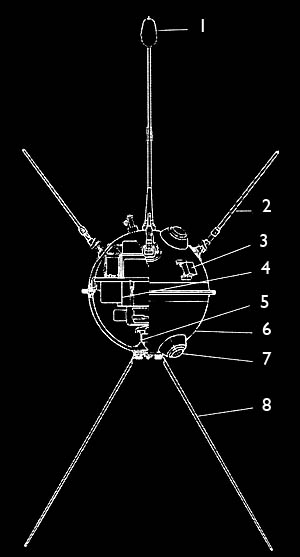

Luna-2 Scientific Pod Sh.Sh. Dolginov designed the magnetometer on Sputnik-3, and on the Luna scientfic pods he installed a three-component metal core flux magnetometer. The device was located on the end of a long spindle, removing it from the influence of the pod's electronics. On Luna-2, the sensitivity of the device was increased by 4, but it still did not measure a Lunar magnetic field. This was a noteable discovery, indicating that if the Moon had a field it must be less than 1/10,000 times as strong as the Earth's.

Cherenkov counters measure a flash of light caused by relativistic charged particles traveling through a block of plexiglas. Lidiya Kurnasova placed a counter inside the pod and (on Luna-2) one in the Block-E stage. The signal is proportional to charge (Z) squared, so it is a particularly good way to measure the rare heavy-nuclei component of cosmic rays. On the Luna-2 mission, a total of 30,000 counts of Z ≥ 2, 3,000 counts of Z ≥ 5 and 100 particles with Z ≥ 15 were detected.

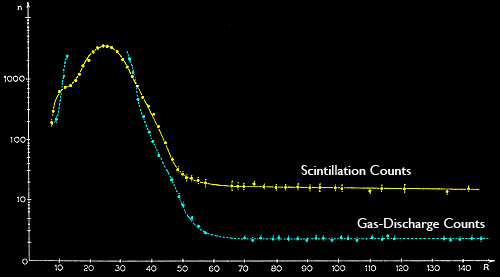

Radiation Counts from Luna-2 Sergey Vernov and his colleagues placed a variety of scintillation counters and gas discharge (Geiger) tubes in the scientific pods and on Block-E. After the experience of Luna-1, he added three gas discharge detectors shielded with copper or lead, to take measurements in the intense outer radiation belt. These can be seen mounted outside the Luna-2 pod, on the base of the magnetometer spindle. Radiation measurements showed a constant level beyond the Earth's magnetosphere, and no evidence that the Moon had a radiation belt -- further evidence that it lacked a magnetic field.

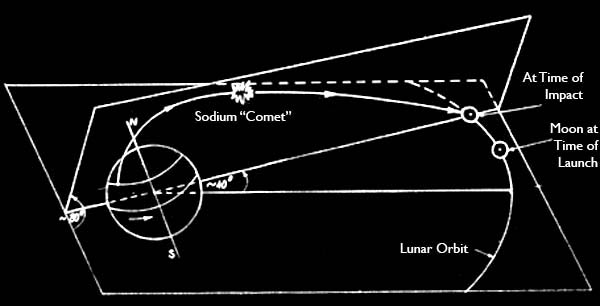

Sodium Vapor Released by Luna-2 Block-E on Luna-1 and Luna-2 carried an experiment to vaporize sodium in space. Four kilograms of the metal was boiled with thermite, and the resulting cloud fluoresced brightly enough to be observed from Earth-based telescopes. This was done to get a precise optical trilateration of the position of the spacecraft, and also to observe the effects of diffusion of vapor in the extremely rarified environment beyond Earth orbit. The thermite evaporator was tested on September 19, 1958 at an altitude of 430 km, using an R-5A sounding rocket. On January 3, 1959 at 00:58 GMT, the experiment operated at a distance of 119,000 km; however, observation of this was poor, due to a large error in the program timer. On September 12 at 18:42:42, the sodium vaporizer was activated at 152,000 km, and the cloud was visible for about 4 minutes at the Almaa-Ata observatory and from three Tu-4 bombers with telescopes installed, to observe the sodium cloud from an altitude of 10 km. The experiment was carried out by Russian astrophysicists Vladimir Kurt and Iosif Shklovsky. They were able to calculate the pressure of the trace of atmosphere at 430 km from the diffusion pattern, which formed a giant orange glow 10-20 degrees across. At more than 100,000 km, the mean free path of a sodium atom was too long to be scattered by interplanetary matter.

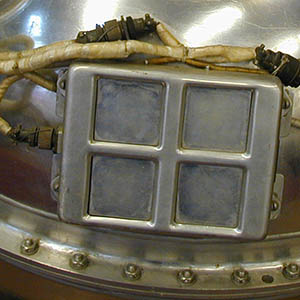

Konstantin Gringauz installed four ion traps on the outside of the pods. These measured interplanetary plasma. As low-energy ions drifted into the region between two charge screens, they would be attracted to them by electrostatic force, creating a small flow of current. On Sputnik-3, he installed two spherical traps that detected plasma from all directions; however, on the Luna missions, the traps were hemispherical.

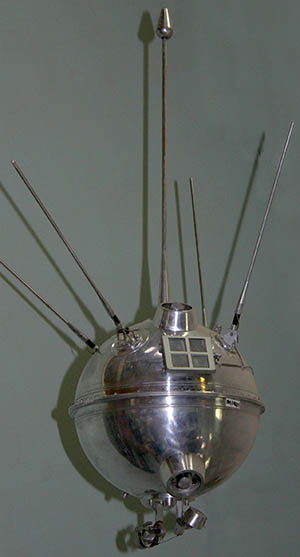

The Solar Wind, An Ion Trap Signal from Tumbling Luna Pod Because the ion traps were hemispherical, they measured the flow of plasma coming from one direction. On Luna-1, Gringauz observed a periodic fluxuation in signal as the scientific pod slowly tumbled in space. This appeared to be the result of a flow of plasma in one direction -- what we now call the Solar Wind. This was probably the most important scientfic discovery of program E1. Before publishing this result, he made a small change on Luna-2. The hemispheres of the pod were offset by 90°, so the four ion traps would be in a tetrahedral arrangement instead of co-planar, as can be seen in images of the Luna-1 and Luna-2 scientific pods above (as an aside, diagrams of early pod design show all four traps mounted on one hemisphere). Again, once the spacecraft was outside the Earth's magnetosphere, a constant flow of plasma was discovered in deep space. This flow of plasma was called the "Solar wind", predicted by some theoreticians, but was not widely accepted until these observations were announced. |

Luna-1 Scientific Pod

Luna-1 Scientific Pod

Schematic

Schematic

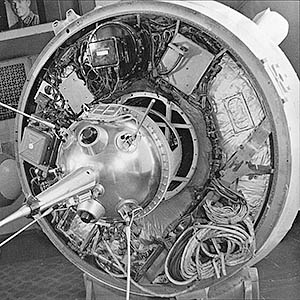

Internals of Scientific Pod

Internals of Scientific Pod

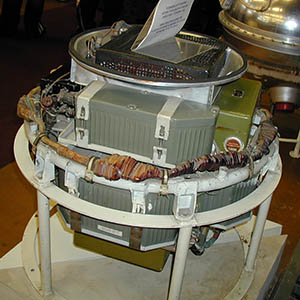

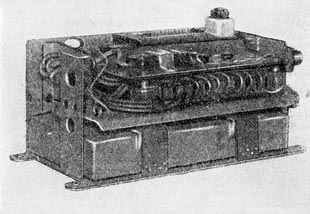

Electronic Gear on Block-E

Electronic Gear on Block-E

Interferometer Antenna

Interferometer Antenna

Another view

Another view

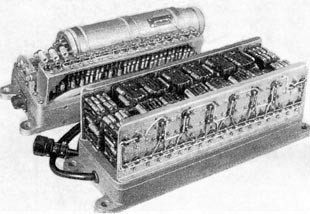

Cherenkov Counter

Cherenkov Counter

NaI Scintillation Counter

NaI Scintillation Counter

Micrometeorite Counter

Micrometeorite Counter

Ion Trap

Ion Trap