From MUDs To Virtual Worlds

Don Mitchell

March 23, 1995

Virtual reality is a computer interface in which the user feels immersed in an artificial space containing representations of data, programs and other users. Despite heavily funded research on immersive computer graphics, the most impressive and complete realization of VR has been multi-user text-based games called MUDs. The sense of immersion on a MUD is imagined rather than sensory, but fast 3D game graphics on PCs suggest that it is technically feasible to make a MUD-like virtual world with a visual interface. Ideally, graphics would make virtual reality more vivid and accessible without hindering the activity and community found on text-based systems.

Virtual reality and cyberspace are popular, compelling concepts. It is becoming feasible for users to interface with computers by immersing themselves in an artificial space containing objects of interest and other users. This is an extension of the current trend to allow users to access and manipulate data directly, hiding the intervening nuts and bolts of the computer itself. And since we live and dream in three dimensions, virtual reality seems to be a potentially natural and rich interface metaphor. Because other users are present in these spaces, social interaction and virtual communities are enabled.

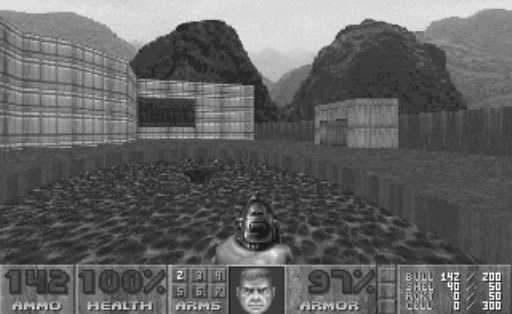

Unlike the 2D desk-top interface, three-dimensional interfaces can create an experience of immersion. Under the right circumstances, users are able to mentally project themselves into a virtual space. One way this has been accomplished has been with 3D graphics; for example, the DOOM game. Another demonstration of immersion has been with MUDs, which are based purely on textual description. MUDs show that a rich, consistent presentation of a virtual space, even without sophisticated display technology, can be vividly experienced in the imagination of the user.

The idea of virtual reality is at least 50 years old. Vannevar Bush proposed many of the basic concepts in 1945, when computers were still in the vacuum-tube era. He suggested that vast amounts of information would be stored in machines and that people might interface with these machines in increasingly intimate ways, including direct induction of images on the optical nerve. Ivan Sutherland built the first head-mounted displays in the late 1960s. In the 1980s, science fiction stimulated a great deal of popular and professional interest by presenting provocative scenarios of virtual reality computer interfaces:

His first stop was Mass Transmit 3. Physically, MT3 was a two-thousand-tonne satellite in synchronous orbit over the Indian Ocean. ...in the Other Plane it was represented as a five-meter-wide ledge near the top of a mountain that rose from the forests and swamps that stood for the lower satellite layer and the ground-based nets.

- True Names, Vernor Vinge (1980)

The most literal-minded research on virtual reality has focused on the problems of display technology and geometrical modeling. Head mounted displays and $150,000 Silicon Graphics workstations make great demos and attract funding, but these efforts have failed to demonstrate an affordable or even a very interesting virtual world. The state of the art in computer graphics is not yet able to generate visually compelling content without enlisting the userís imagination. To do that, there must be a well-constructed, consistent model of a world on the other side of the display.

In 1978, the first text-based, multi-user adventure games, called MUDs, appeared; and by the late 1980s, these systems had evolved into the most sophisticated demonstration of virtual reality. MUDs represent a world of interconnected rooms, populated by active objects and avatars representing users. Actions and descriptions are displayed only via text, but users learn do develop a vivid experience of immersion in a virtual space as they read and type. As computer programs, MUDs represent an underground evolution of operating systems based on persistent, active objects. As virtual worlds, MUDs have encountered and solved many of the technical and social problems of how to immerse users, structure virtua space, and manage communities.

The most successful MUDs, such as FurryMUCK or LambdaMOO, are thriving communities of 9000 or more users. Some are still structured as violent adventure games requiring considerable time and effort, and others are purely social spaces where users are free to build and interact. Any effort to construct virtual worlds must not ignore the lessons offered by these text-based environments.

While MUDs demonstrate the importance of underlying structure versus display technology, it is also true that reading and typing text can be burdensome. World-Wide-Web browsers like Netscape and Mosaic have demonstrated that users enjoy building and exploring multimedia environments. Computer games like DOOM or Virtua Fighter have demonstrated that affordable computers can generate interesting 3D graphics. Users enjoy the immersiveness of 3D games, and the limited resolution of these graphics indicate the importance of having an underlying context of interest.

The technology seems to be present today, but many attempts to combine MUDs, the World Wide Web, and 3D graphics seem ill-conceived. ChibaMOO and some other MUDs have WWW interfaces that allow users to augment descriptions of objects with audio or GIF-formated images; however, the web protocol itself seems fatally flawed by its inability to allow efficient interactively between clients and servers. The VRML project seeks to augment the web protocol with a geometrical modeling language for describing 3D spaces, but the lack of multi-user interaction makes this typical of many other display-centered approaches.

This report discusses and advocates an approach strongly grounded in MUD systems. The goal is to understand what makes MUDs successful and to suggest ways to augment that experience with graphics.

MUDs are the most tangible example of virtual worlds that we can find and study today. The "display technology" of MUDs is simply text, and so the experience of virtual space is imagined rather than sensory. Nevertheless, for a small, readerly audience of users, MUDs are rich and immersive. By avoiding the difficult problems of computer graphics, MUDs have been free to explore other aspects of virtual worlds; how to structure space, how to represent the user in the space, and how to deal with behavior and community.

MUDs began as multi-user text adventure games, but in 1987, Jim Aspnes at CMU made a critical change. He threw away the game-play aspect and simply allowed users to freely describe themselves, build on to the space and socialize with each other. His TinyMUD system spread across the internet like a virus and rapidly evolved into complex programmable systems. This section will discuss how social MUDs create a sense of space, how the user is embodied and active in these spaces, and how a sense of community is sometimes achieved.

The first impression a user has of a MUD is the space itself, and exploring it will set their sense of where they are and whether or not they want to stay. The structure of space in a MUD is similar to what was found in early single-user text adventure games, like Crowtherís original ADVENT game. In addition to being multi-user, current MUDs are designed to allow on-line users to build onto the game.

In TinyMUD, complex worlds were constructed from four simple object types: rooms, exits, things and players. All objects had a set of basic properties such as a name, a full-length description, a contents list (what is in a room or what a player is carrying), and activation messages. Later versions of this program (e.g., TinyMUCK, TinyMUSE, and MOO) included full programmability of object behavior.

The virtual space itself is defined by a network of rooms interconnected by exits. The room object contained players and things. When a user entered a room (by moving their player object there), its description would be displayed, suggesting their presence in a place. On more advanced MUDs, room descriptions are more dynamic, showing players sitting on furniture for example. Text can evoke sights, sounds, smells and emotions:

Nocturne

Moonlight pours through an open window, as rain beats a steady patter on the balcony to the west. The floor is a patchwork of dark-coloured stones, the walls a solid ebon rock, gleaming with a lunar glow. The large bed lies unmade, soft pearl duvets shimmering with a chill draught, making it seem all the more seductive.

The user navigates by typing the names of exits that connect the room theyíre in to other rooms. In the example above, the description suggests the existence of an exit called "WEST" which would lead to the balcony. An activation message can be printed when the user moves, describing the journey. Exits also have a description which the user sees if they type "LOOK WEST".

Some rooms in a MUD become important gathering places where users can rendezvous or just hang around and meet people. The creators of a MUD may attempt to define these spaces. but itís hard to determine where users will choose to hang out. On the original TinyMUD, a village square was designed to be the social nexus, but in fact a room created by one of the users soon became the heart of the MUD:

THIS is the Rec Room!!!!

This large, darkened room has no obvious exits. A crowd relaxes on pillows in front of a giant screen TV, and there is a fully stocked fridge and a bar. By the TV is a black box with buttons marked with the numbers 2 through 13 and the letter U. A glass phone booth stands in the corner.

While the Rec Room says it has no obvious exits, in fact hundreds of exits connected this location to all the major sites on the MUD, and the owner of this room wielded the power to grant permission to link exits to other userís rooms. This room was a social meeting place, a navigational hub, and a source of political power for its owner. Even though there is no game play, part of the effort in being on a social MUD is to make spaces that will be admired and used.

Users navigate on a MUD by looking and going through exits. To illustrate this, here is a short transcript of a walk through an early TinyMUD called Islandia, which was shut down in November of 1990. User input is denoted in capital letters after a ">" prompt. Notice that some exits donít actually go anywhere! In the example below, "SIT" and the last instance of "WEST" are simply used to generate an evocative message:

>LOOK

Town Square

A large oak tree spreads its branches over a wooden kiosk covered with announcements in the grassy center of the square. Park benches line the sidewalks amidst flowery shrubs. You see the library to the northwest, the post office to the southeast, the homeless shelter to the southwest, and the hotel and convention hall to the northwest.

>SIT

You sit down on a park bench.

>LOOK WEST

The duck pond is to the west, and banners and pennants are beyond it. Lucky for you, there is a wooden bridge upon which you can cross, if you can get past the horrendous crowd on it.

>WEST

You head for the bridge, hoping to push your way across.

Crowded Wooden Bridge

You stand in a huge crush of people trying to cross a nasty wooden bridge to the other side of the duck pond. There is a mermaid beneath the bridge, and a very nasty beggar whom you must pass to go west. Maybe heíll not notice you.

>LOOK DOWN

Itís a steep climb, but you could probably make it. Besides, thereís the mermaid down there.

>WEST

The slimy beggar gets in your way. Alms! Alms for a slimy beggar!

>PAY

You drop a coin into the beggarís cup, feeling rather charitable, and he allows you to pass west with many cries of a thousand thanks, noble lord!

Virtual spaces can easily become vast and complex. On some MUDs, the user can easily teleport to any known location or the location of any user. Experienced users often prefer this, since they have already explored the space extensively. Some MUDs try to encourage more themely forms of transportation and give some guidance to interesting places. FurryMUCK, in the course of its six years of operation, has developed a number of interesting navigational aids and guides:

Things are objects that can be located in a room or carried by a user. On TinyMUD, they were mainly persistent objects that could be used as props, containers, food, clothing, gifts (rings, flowers, etc) or simply act as amusing ornaments like this strange object kept in the Rec Room:

icky thing

This icky thing is slimy and sticky and nasty and stinky. Dust and unidentifiable crud sticks to the outside. Your stomach lurches just knowing this thing exists in the same universe as you. Gross! You think you saw it move, just a tiny bit..

On the first social muds, things acting as notes were placed in a post office to send asynchronous messages to other users. In later MUDs, internal email, bulletin boards and newspapers were implemented and formed an important part of the community life on these systems.

In later MUDs, things (and other objects) could be programmed to respond to commands and to the environment. One of the most complex type of programmed objects is the automaton or "bot". For example, when a user (such as Nigel) enters Equine Central on FurryMUCK, they are greeted by a bot:

Nigel walks in through the doorway to the south.

Honey the EC Receptionist looks up from her hay-munching with a grassy mouthful and her eyes go wide upon seeing Nigel. She pituiís out the unchewed hay and welcomes him to Equine Central.

Automatons range from simple "Eliza" programs that respond in a primitive way to speech to complex finite state machines that can mimic people or animals with changing moods and descriptions. They are used to simulate pets, waiters, chiming clocks, you name it.

Player objects (or "avatars" as some call them) represent the users themselves within the virtual space. In some sense, the player acts as a cursor, defining the current location and viewpoint of the user and the "room focus" where communication occurs. Players have a description that is viewable by other users, and people take great delight in designing the appearance of their player.

Many users seem to project themselves into a virtual space, in their own imagination, and inhabit the body defined by the player. By setting the description of a player, and subsequently controlling its behavior on the MUD, users construct a persona which may be quite different from their real-world selves. It is not unusual for people to have a player with a different gender or even a different species. Here are a few examples of player descriptions:

legba

Wearing, as usual, a borrowed body. She sails about, this one, massive and magnificent as an antique schooner, wearing a muumuu bright with flowers of a variety and color not often found together in nature. Her heavy-Lidded imperious gaze fixes you for a moment and her mouth compressed in what might be either manifest disapproval or suppressed amusement. Her hair floats in a frowzy black halo around her face. She has a deep, rich laugh and very small feet which are usually wedged into pink mules.

Nigel Unicorn

Standing 16.2 hands, Nigel Unicorn stands before you, Blacker than black, blacker than the darkest night, blacker than the deepest mine, blacker than the deepest space. The one touch of color that breaks the darkness of his form are his eyes which depending on the light, shift in color from gold and green, blue and red. His horn appears to be spiraled in shape, about 30cm long and similarly black, but the longer you stare at it the more disoriented you become, and you feel as if you are being drawn from yourself, pulled from here to....somewhere.

While stocky in build Nigel moves gracefully and when he notices you watching him he prances around a bit proudly shaking his long mane and flipping his tail. He greets you with a happy whistle, and whickers gently to you, happy to make your acquaintance.

"legba" is a graduate student in literary theory, and her descriptions are vivid and amusing. "Nigel" is an electrician in real life, and his player is a classic example of a "Furry", a strange but popular subculture of MUD enthusiasts who role play anthropomorphic animals.

On chat lines, like IRC, users are not well embodied in a virtual space. Literary theorists will claim that the on-going discourse of a chat line does construct a world and user bodies, but these constructions are ephemeral. MUDs allow a persistent definition of identity and of virtual body. Experience with MUDs seems to indicate that some users enhance their sense of immersion by increasing the sophistication of their simulated body. Other users find embodiment in virtual reality to be a disturbing concept.

One of the largest MUDs on the internet is LambdaMOO, a MUD run by Xerox PARC. In 1993, a major social upheaval illustrated some of the controversy and emotion surrounding players and the embodiment of users in virtual reality. The controversy centered around a very sophisticated player object programmed by a user known as Quinn. The Schmoo Player Class, and a later version called the Revenant Player Class allowed the user to construct a virtual body with more flexibility than a static paragraph of text.

This player class had separate body parts which could be described individually: head, chest, arms, hands, groin, legs and feet. When you looked at one of these players, you would see the concatenation of these descriptions. Usually this was a description of a nude body, but this player class could wear clothing that would selectively cover parts of the body (or other items of under clothing) and replace those portions of the description with a clothing description.

This player class became extremely popular and challenged the rulers of LambdaMOO in two ways. First, Quinn himself became politically powerful as the leader of the schmoo players. Secondly, this player class forgrounded the controversial activity of virtual sex. The schmoo clothing items were programmed to generate messages associated with dressing, undressing or being stripped by other players. Some users objected strongly to the practice of virtual sex. Eventually, Quinn was expelled from LambdaMOO. The subsequent popular protest not only resulted in Quinnís return, but ultimately lead to the replacement of the oligarchy of rulers with a democratic form of government on that MUD.

Another example of strong embodiment in virtual reality are the so-called Furries. This subculture first appeared on the original TinyMUD as a group of users who described themselves as anthropormophic animals. They were somewhat controversial, and eventually formed their own MUD called FurryMUCK, which today is one of the largest and oldest MUDs on the internet (about 6000 users). Furries go to great length to create sensual bodies; sleek fur, slitted pupils, sharp claws. FurryMUCK is a remarkably friendly, playful MUD with a strong identity as a community.

Users can become quite emotionally involved in the creation and inhabitation of their player. On a MUD called Post Modern Culture, a group of artists decided that users were creating players that were too clichť and representational. As an artistic and political experiment, they decided to programatically alter the gender and appearance of players. Users protested strongly, referring to this experiment as "genderfuck", and many of them simply left the MUD.

Users on MUDs communicate with text messages, usually broadcast to the players contained within the same room. As in chat systems, users can simply talk, but an important style of communication that emerged on TinyMUD is emoting, where a player describes a gesture in the third person. For example, if we were operating a player called Bob, we might see the following simple exchange:

>SAY HELLO EVERYONE!

Bob says, "Hello everyone!"

Alice says, "Hi Bob. Howís it going?"

>EMOTE SITS DOWN AND SIGHS.

Bob sits down and sighs.

Alice looks concerned.

Alice says, "Whatís wrong Bob?"

Emoting is a particularly interesting communication feature of MUDs that allows users to narrate about themselves in the third person, rather than communicate in the form of speaking (as in a chat system). Emoting is an important mechanism for MUD users to construct imaginary state about the world, an imaginary action or their state of mind.

Here is a sample of some MUD communication between two friends (and some other bystanders) on FurryMUCK:

Trevor says, "I live in the Woody Willow north of Feline Park."

Nigel whips out a map from his saddle bag and lays it on the ground puzzling over the best route to Trevorís treehouse.

Trevor just reheated some left-over Spanish rice and seafood.

Nigel sniffs at the food trying to determine if it would be good for a unicorn... satisfied that it at least wouldnít kill him he buries his muzzle in the pot and gulps it all down...

Trevor eeps! Then laughs.

Nigel says, "Letís see if I take the step disks for 5 stations north of the park turn east, leap to BoingDragonís jump room, and call a taxi to the acme Truth or Dare pool hang a right and fly straight up to the west corner of the part I should be able.... hmmm why donít you just carry me."

Rena winks at Nigel.

Nigel whickers hello to Rena.

Nigel canters around Trever in a small circle...

Trevor bows to Keats.

Trevor says, "OK, letís go Nigel."

Nigel nodity nods.

A surprising amount of communication on MUDs is in the form of emotes. In combat adventure MUDs, emoting was not allowed, because users could use it to subvert the simulation of the game. Casting spells and wielding weapons were controlled by special commands, and it was felt that arbitrary emoting could disrupt the consensual illusion of the world (e.g., by emoting the launch of a nuclear weapon in a bronze-age setting). Users still manage to emote by subverting activation messages.

Successful MUDs have evolved beyond being games or "interactive fiction" to become large, long-lived communities on the internet. FurryMUCK has about 6000 users and has been on-line since 1990. LambdaMOO came up about a year later and has about 9000 users today. Chat lines and bulletin boards also popular, but they lack a virtual geography to explore or create mood, and chat lines even lack persistent player identities.

The Doblin Group, a prominent Chicago consulting firm, recently completed a million-dollar effort to research the concept of community. They condensed a mountain of published research into six properties measuring the strength of a community: effort, purpose, identity, organic, adaptive, freedom.

A problem with chat lines is the total lack of effort, obligation and responsibility on the part of the user. They log in to be amused and can be rude or simply disconnect the moment they get bored. MUDs are stronger in this area because the user has a persistent player and perhaps other artifacts they have built. Although the user is usually anonymous, they have an investment in their player, and they have an incentive to be popular and creative in order to get the most out of the MUD.

MUDs generally lack a strong sense of purpose, except as a game or meeting place for friends. Attempts to build MUDs around some goal like the MIT Media Labís MOO, which was designed to bring researchers together, have generally not been very successful. Thus far, those MUDs have simply been too boring to attract and stimulate people.

MUDs vary in their sense of identity. Most have a theme, particularly the adventure-game MUDs, and users often have a sense of pride in one or two particular MUDs after they have invested time there. The one outstanding example of a MUD with a strong sense of identity is FurryMUCK. Furries view themselves as a counter culture. They meet in real life at large conferences, they have generated an enormous collection of artwork, poetry and short stories which can be accessed via their web page (www.furry.com), and some of them even live together in urban communes known as "Furry houses".

Early MUDs were games with an inflexible structure designed by their owner/authors. Companies like Simutronics still produce such systems, but they lack the organic, co-constructed nature of modern internet MUDs. The Schmoo Player Class or The Rec Room are good examples of the rich and unexpected phenomena that have resulted from end-user authoring and community feedback.

Are MUDs very adaptive? As computer systems, perhaps not. So far, the technology has not scaled well to large communities because MUDs are based on centralized servers. While distributed MUDs have been attempted, this has proven to be too difficult for the creative but inexperienced programmers who develop MUD servers. As communities, some MUDs have survived for as long as six years. Personality clashes, anti-social users, and power struggles occur on almost all MUDs, and some of them fail as a result.

One of the great attractions of MUDs is the freedom it gives users to transcend almost any limitation of the real world. Uses can define a body and personality for themselves, they can create fantastic places or objects, and they can explore social interaction. At the same time, most MUDs do not have a free form of internal government, and in the worst cases, players are subject to the petty whims of the MUD rulers.

As communities, MUDs vary in quality, but there is clearly a strong potential. A few examples, like FurryMUCK, have a powerful sense of community, and some users act like loyal citizens of a virtual world. Some MUDs are simply games, although combat adventure MUDs can have a sense of community. Users socialize and even fall in love on some of those game-oriented systems. Many large social MUDs, like Xerox PARCís LambdaMOO, do not have as strong a sense of community as FurryMUCK, but its users feel a sense of pioneering, and public political forums stimulate involvement.

I played for a short while on MUD II, the original English MUD, and pretty much died the moment I stepped out of the safety of the "Elizabethan Tea Room". My playerís name was "Patroclus", a prince from the Iliad, and within minutes of logging in, someone paged me with "Hector is coming to get you!" (Hector killed Patroclus in Homerís epic). The users were educated, arrogant and displayed a complex mix of cruelty and fair play. New users on a combat MUD are called "newbies", British boarding-school slang, and they are sometimes helped and sometimes humiliated by more experienced players.

Social MUDs are not this bad, but on a poorly-managed MUD like LambdaMOO, a newbie may find it hard to get help, may be treated rudely by some players, and will find it difficult to build new spaces in an old MUD with an overly full database. FurryMUCK is still a very positive experience for new users, and the attitude is extremely helpful and friendly. On Dhalgren, a MUD run by the author, an entertaining tutorial, in the form of a cave to be explored, was constructed to help orient new users.

Unlike chat systems, MUDs support an explicit representation of virtual space. The user is situated in rooms or areas with descriptions, often via direct second-person address ("You stand in a huge crush of people..."). The space is populated by objects which can be looked at, picked up, carried around and dropped. It is also populated by avatars of other users who can also be looked at. Users navigate this space by typing directions to walk in, taking them from room to room. As spaces become large, additional mechanisms need to be added for users to discover and travel to places of interest.

MUDs represent the user as a player object in the virtual space, providing a persistent identity with a name and description. Users enjoy creating the appearance and behavior of a new persona, and viewing other players increases the sense of being immersed in an inhabited space. Embodiment is enhanced for some users by player objects with more structure (clothing and body parts). Friendship and sex both occur in virtual spaces.

Users communicate and gesture with text, and the most powerful communication device invented on MUDs is the emote. Emoting allows users to augment talking with third-person statements that indicate moods, thoughts and actions. Combat MUDs attempt to repress emoting to enforce consistency with the game, while on social MUDs, emoting accounts for about half of peopleís communication.

Some MUDs, like FurryMUCK, have become large, long-lived communities. MUDs are free and organic, allowing users to socialize, explore and create. Because the space and the players have some persistence, these communities require some effort to make friends and invest in the development of an interesting player. Some, but not all MUDs have a strong sense of identity and purpose. Attracting and entertaining new users is also an important issue to keep in mind.

The technology exists today to create a more direct, sensory experience of immersion in a virtual space, but thus far, there has not been much experience with how to apply this technology. Text can be highly evocative, but there is much to be said about showing the user what a virtual space is like instead of making them read about it. People can absorb visual information rapidly and effortlessly, and moving rapidly through a space is thrilling. The remainder of this report discusses some of the experiments and questions about how to use graphics in the representation of a virtual world.

The immersiveness of 3D graphics was repeatedly demonstrated in SIMNET, a large military war-game simulation system that combined flight and tank simulators in multi-user exercises. The tank simulators allowed the user to drive around in a 3D virtual environment of textured terrain, vehicles, explosions and smoke clouds. The graphics display itself was only 320 by 200 pixels drawn at 15 frames per second. In addition, there was an audio communication system that simulated battlefield radio.

An interesting lesson learned from SIMNET was that the users felt immersed even though the display had a rather poor resolution. Soldiers still found the system thrilling to use, and they "saw through the technology", as one expert described. The 3D world was comprehensible and consistent, and the userís imagination could fill in the missing resolution. The overall experience was also enhanced by the interaction with team members over the radio.

A courtyard scene from DOOM

The popular PC gamed, DOOM, was a revolutionary development that took graphics researchers and the game-playing public completely by surprise. This program allowed the user to walk through a 3D world, using only a 33 Mhz 80486 processor and VGA frame buffer of a common PC. Two key inventions made this possible: a restriction of the 3D geometry that allowed visibility to be computed in two dimensions, and a clever texture-mapping algorithm that rendered surfaces in perspective along lines of constant distance.

DOOM is an example of a full 3D graphics, where the user can walk anywhere and look in any direction. Motion is restricted to the two dimensions of the ground, using the arrow keys to turn left or right and walk forwards or backwards. Objects are picked up by running over them, and devices (switches, doors) are activated by standing in front of them and pressing the space bar. It is a multi-user game, and the players (and objects and monsters) are represented as 2D sprites. The user sees the world in first person, viewing the world through the eyes of their player.

A Western saloon scene from Alone In The Dark

A different approach to visualizing a 3D world is taken by the game Alone In The Dark. This game shows the player in a third-person view instead of through his eyes. Space is represented as 2D artwork, drawn in proper perspective, and the player and other objects are represented by articulated 3D geometry. The user can move the player with the arrow keys, just as in DOOM, but the view of the world is made up of discrete pieces of art presented as different camera shots of the world.

The examples above are violent action games or simulations rather than social spaces, but they represent the two basic approaches to the representation of worlds. The 2D approach of Alone In The Dark is almost MUD-like in that space is represented by a collection of discrete scenes. Each fixed background image represents a "camera shot" of some part of the space, and while the avatar can be moved around, at some point, there may be a transition from one scene to another. An advantage of this representation is computationally cheap rendering. Only the avatars really need to be rendered at full frame rates, while in a 3D, first-person environment, the entire screen can change while the player moves. Memory usage depends on the quality of the 2D backgrounds and how many viewpoints of the space are allowed.

Authoring this type of 2D representation requires planning and drawing perspective art. In the case of Alone In The Dark, this clearly required professional artists. An interesting alternative is demonstrated by the game, MYST, in which the authors built a 3D model and used a ray tracer to automatically generate perfectly consistent and correct 2D perspective scenes. In a full 3D game, this is taken to the extreme of authoring a 3D model and rendering perspective scenes in real time from any viewpoint the user desires.

Full 3D virtual space requires a continuous representation of 3D geometry, rather than a discrete set of 2D views. Given the current state of the art in real-time rendering on PCs, there are two feasible representations for objects and space: texture mapped polygons, and voxel height fields. The latter is a specialized technique used by some games for outdoor terrain, although Magic Carpet actually uses textured polygons for terrain. A special case of texture mapping is the use of environment maps for distant features like sky or mountains. The "outdoor engine" in the new game, Terra Nova, blends between these three methods, using polygons for nearby features, voxels for medium-distance terrain, and environment maps for everything beyond.

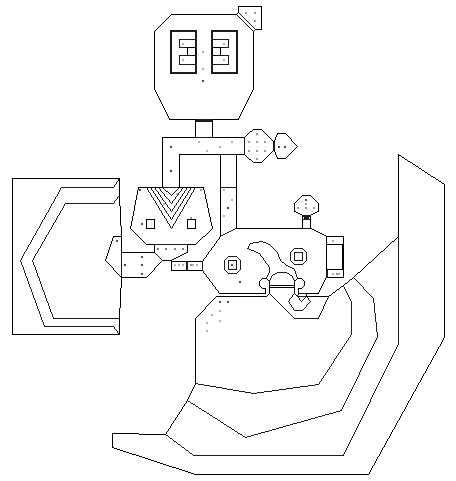

Much of the richness of a 3D environment can be captured by a 2D floor-plan model, as demonstrated by DOOM. In this approach, the world is treated as a one-story building with vertical walls, sections of floor of varying heights, and an optional ceiling. This paradigm is sufficient to model stairs, tiered courtyards, pedestals, pools, windows and skylights. Because it is easier to author than general 3D models, considerable content for DOOM has been authored by some enthusiastic end users.

A typical DOOM floor plan

Unfortunately, games like DOOM have very purposefully modeled spaces that are full of tension and threat; walls riddled by bullet holes or splashed with blood, dimly lit corridors, hidden doors, and confusing mazes. These games demonstrate promising new technology, but they have the wrong esthetics for social spaces.

What will people do in a virtual world, and how can graphics enhance their experience beyond what is found in MUDs? This is a poorly understood problem. We know what people do on MUDs: explore, build, play games, fantasize sexually, and chat. From this emerges friendships, feuds, politics, artwork, and community. It is difficult to even speculate how graphics or other media might enable entirely new experiences and behavior, hitherto unseen on MUDs. The immediate goal is to improve the quality of the userís experience.

New users typically engage in exploration, learning what the virtual space contains and deciding whether or not to invest time there. This seems like the most obvious opportunity for graphics. First-person full 3D spaces quickly immerse the user and give the thrill of motion and discovery. Seeing into the distance can give an overview, as can explicit maps. In third-person views, navigating the player around an area is clumsy (an annoying feature of games like Alone In The Dark), but clicking on destinations seems to work well (as LucasArtsí games demonstrate). Full 3D representation of space gives the user a greater sense of motion and freedom, allowing them to approach and inspect any object that interests them or to look around corners and behind things. 2D backgrounds and the texture images mapped on surfaces in 3D can be interesting and high quality, since they are rendered or painted off line.

The representation of the userís virtual body can also be 2D or 3D. Little can be said with certainty today about which provides a greater sense of immersion or embodiment. 2D avatars may be easier for end users to author, perhaps by scanning in photos or drawings. Gesture and animation of 2D avatars requires storing different poses and aspects. 3D avatars can be more easily animated, and a single model can be transformed into different poses or seen from any direction. It may be more difficult to author 3D avatars, and perhaps difficult to overcome the esthetics of polygonal shapes. Segaís game, Virtua Fighter, gives an example of human figures modeled with a fairly small number of texture-mapped polygons:

Polygonal avatars from Virtua Fighter

In a recent survey of users on LambdaMOO, people reported that 57 percent of their time was spent socializing; which is to say, communicating with other users. Live audio would allow users to speak directly, although with more than two users communicating at a time, scrolling text enables complex multi-threaded conversations without the problems of users interrupting each other. This report has neglected the subject of audio, but clearly, speech, sound effects, and music are important additions to a virtual world. But it seems likely that the first virtual worlds will be based on text with graphics.

When asked about graphics. most MUD users have a hard time thinking of much that it can do to improve their experience. Avatar gestures and facial expressions can augment communication and replace some of the simplest uses of emoting on MUDs, but it seems unlikely that the elaborate moods, thoughts and actions of emoting could be expressed graphically. Graphics can certainly set a mood, just as rooms on MUDs do. Finally, knowing who is present at a location is clearly illustrated by a visual display. On MUDs, users frequently type "LOOK" or "@CROWD" just to remind themselves of who is present in a room.

There are some reasons to think that a third-person view would be best for group communication, because it gives a wider angle of view that can include everyone, and it allows the user to see their own avatar in context, just as one sees their own emotes on a MUD.

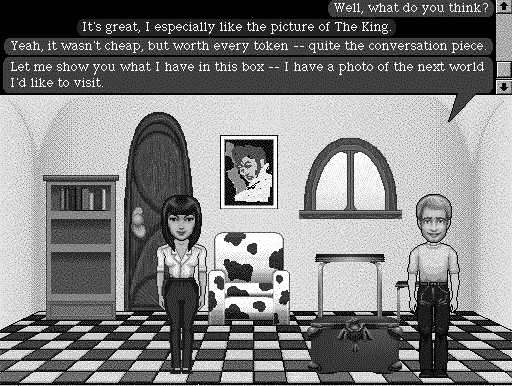

A scene from Worlds Away

Lucasfilmís Habitat system, and the current version of it called Worlds Away gives a fascinating example of a social space enhanced with graphics. Their system uses 2D graphics, sound effects, and textual communication. As illustrated above, a scrolling MUD-like text windows is cleverly combined with aspects of the comic-book speech balloon. The bodies can turn and sit, and the heads can have versions that display expression. Because the settings have a fairly limited 2D view, it is easy to spatially associate speech with a player by printing it above them and displaying an arrow (as seen above) to the most recent user to talk. In a full 3D world, connecting speech with players is more difficult. The first solution that comes to mind is to simply have a scrolling MUD-like text window below the graphics display.

Conspicuously absent from Worlds Away is the ability to emote. The user can "say" or "think" something, but they cannot narrate an arbitrary action or statement. Emoting is a dilemma. As in combat adventure MUDs, allowing the user to emote could create inconsistency. Graphics cannot visually display complex actions that might be implied by emoting. Should the inconsistency be allowed, or should user communication be restricted?

Combat adventure MUDs have many special-purpose commands instead of general emoting. These commands implement fighting and game play, and even on social MUDs, commands like "take", "drop", or "go" actually do perform an action. Emoting does not perform an action on the world, but simply describes an imaginary action. In a graphically displayed world, as many actions as possible should be animated to give a sense of efficacy, giving the user a sense of acting in and upon the world.

I believe emoting is too important and expressive to be disallowed. Users will find their own idioms of communication, and if emoting is not allowed, they may simply invent a convention of speech to implement it. I would advocate giving the user various channels of communication. Different commands could say or emote as in a MUD. Other commands might place text into a balloon over their head or into a narration box in the upper left corner of the frame. Given a various means of expression, no doubt new styles of communication will emerge.

MUDs can immerse users in an imaginary world described with text. They provide a persistent space that can be explored, changed and constructed by users. They create an embodiment of the user in the virtual world, into which they can project their agency and meet other users. The first MUDs were thought of as games or "interactive fiction", but they have evolved well beyond those notions into complex social environments.

Adding graphics to MUDs is technically feasible, and in theory it should be able to replace some of the burdensome aspects of reading text with a more direct sensory experience. Visualizing and exploring the virtual world is clearly enhanced by graphics, but adding a graphical component to communication is a subtler problem. First-person viewpoint, like DOOM, works well for exploration. When communicating, users may want to switch to a third-person view that shows them and their gestures in context with others.

Current graphical VR proposals like VRML have focused only on rendering and geometrical modeling, which may not be the hardest or most important problems. VR is more than a "3D document". In a distributed multi-user environment, it is important to make the models dynamic, allowing motion and updates to geometry. Difficult problems of distributed cache consistancy and updating replicated data must be addressed in order for the system to scale up to large numbers of users. Finally, there is the problem of user interface design; allowing users to communicate with each other, navigate in the space and interact with objects. Experience with MUDs provides some clues to how virtual spaces should be structured and how users will interface with them.