Nikola Tesla's Investigation of High Frequency Phenomena and Radio Communication (Part I)Donald Mitchell Pelican Rapids, Minnesota, 1972

PrefaceI became interested in Nikola Tesla several years ago, in 1970, while working on a large Tesla coil with some friends. I had heard that the Tesla coil was invented in an early attempt to transmit power by radio, but this was dismissed as the futile experiment of some-turn-of-the-century scientist who had no real understanding of radio. About a year later, I obtained a copy of Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla by John J. O'Neill. This is generally considered to be the best biography, although there are half a dozen others that I know of. Like anyone who reads this book, I was fascinated by Tesla's life and accomplishments; in particular, by this work in Colorado Springs. Unfortunately, there was no technical description of the equipment that Tesla used except for some speculation that was totally false. I have never been able to find any book or person who knew any technical details of the wireless power system he was testing in Colorado, but I did know that it was not as naive as a radio wave system. (Naturally radio would not be a practical means of power distribution since it is subject to the inverse square law.) This report is the outcome of a very careful study of early photographs, articles, patents and books and contains as much technical detail as I could find. It is still very incomplete, but unfortunately, little information exists on Tesla. After Tesla's death in 1943, several trunks of papers, records and equipment were removed from his room. These papers are now in the Nikola Tesla Museum in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. To my knowledge, scientists from this country have never studied them. [DPM - some of these notes were published in 1978] IntroductionNikola Tesla was born on July 10, 1856 and died on January 7, 1943 [1]. During his lifetime, the technology of modern radio and electric power was born. Tesla made many important contributions in these fields. The most important and the most famous of these was the invention of polyphase current. This allowed practical distribution of electricity for long distances and enabled efficient electric motors. He developed generators, transformers, and motors both of polyphase and split phase. Today these inventions literally turn the wheels of industry. Tesla knew that the world would need more and more power if it was to advance, and he devoted his life to developing new means of producing and distributing power. The most fascinating project that Tesla conceived was a plan for transmitting electricity without wires. This project took up more than twenty years of his life and was never completed successfully. However, the discoveries that Tesla made during this time almost led to the creation of a global radio network decades before the present one was first established. Invention of the "Tesla Coil"Tesla's first work with high frequency electricity began in 1889 [2]. A year earlier, he had received $1,000,000 from George Westinghouse for his polyphase patents, and with this, he planned to begin researching new ideas. Tesla occupied the entire fourth floor of a six-story building at 33 and 35 South Fifth Avenue in New York City [3]. Ever since 1887, when Heinrich Hertz had discovered radio waves, Tesla had been fired with the ambition to explore the range of frequency between his alternating current and the extremely high frequency vibrations of light [4]. By 1890, he had made a great deal of progress. His first experiments were with a unique new high frequency alternator [5]. This was made up of a steel disk 30 inches in diameter with 384 poles like the teeth of a cog that had zigzag windings on them. This disk revolved within a fixed ring that had 384 inductor poles. When this machine was turned at 3000 rpm, it produced about 200 volts at 9600 to 10,000 Hz. Tesla was the first man to work with such a device [6]. Later machines of somewhat different design produced up to 30,000 Hz.

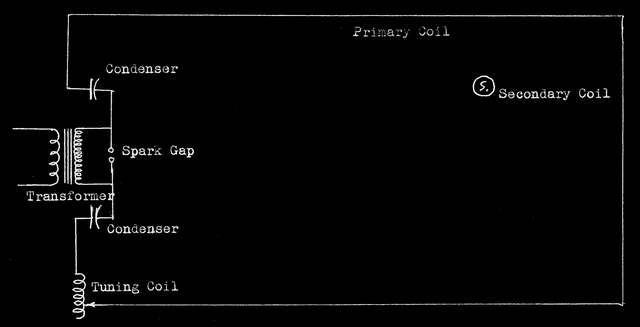

With these alternators, Tesla discovered the basic principles of tuning. Although electrical resonance was known at that time, it was primarily a theory that rarely manifested itself. However, at the high frequencies that Tesla was using, the devices would not function unless tuned to resonance. In experiments with the alternators, he made use of induction coils to step up the voltage. At first, ordinary coils were used, but Tesla soon found that by removing the iron core, he could improve the output of the coils. In some instances, the coils were immersed in boiled linseed oil for insulation. Tesla may have been the first electrical engineer to use this now common technique for insulating high voltage. Using partially evacuated glass tubes, Tesla began extensive investigation of lighting systems using fluorescent tubes much like modern neon lights. This was not original work at that time, but several discoveries were made during these investigations. Tesla was well aware of the heating effects of high frequency currents and fields, and in 1891, he became the first man to suggest the use of radio frequency warming for therapeutic purposes [7]. Tesla was not satisfied with the alternator and wanted a more powerful and less cumbersome source of current that could produce higher frequencies. Although the alternator could produce sufficient current for Tesla's experiments, it was very unreliable as Tesla stated in the following section of an article on alternators: "The writer will incidentally mention that anyone who attempts for the first time to construct such a machine will have a tale of woe to tell. He will first start out as a matter of course, by making an armature with the required number of polar projections. He will then get the satisfaction of having produced an apparatus which is fit to accompany a thoroughly Wagnerian opera. It may besides possess the virtue of converting mechanical energy into heat in nearly perfect manner [8]."For a more reliable power source, Tesla took advantage of the fact that when a capacitor discharges through a coil, the energy oscillates rapidly back and forth between them. This formed the basis of the Disruptive Discharge Coil, or as it is known today, the Tesla Coil. In this device, a high voltage induction coil or transformer charges a bank of leyden jars or other high voltage condenser. When the voltage on the condenser builds up to a high enough level, it discharges through a spark gap and a primary coil. The current oscillates at a frequency that may be several million Hertz. A large secondary coil is energized by the primary coil and reaches very high voltages. These first coils were of the same type used with the alternators. They produced arcs about five inches long, indicating a voltage of about 100,000 V was being produced [9]. In the years of 1891 through 1893, Tesla gave many lectures in America and Europe on his work with alternating current [10]. At these, he demonstrated most of the basic equipment necessary for wireless telegraphy, such as tuned and coupled free oscillating circuits, the choke coil, and rotary and series spark gapes. [DPM - quenched gaps, these open the circuit quickly when oscillation dies down, so the condenser can start recharging.] First Work on Wireless PowerTesla, having invented the method of transmitting power long distances on wires, seemed to want to out do himself when he became fascinated by wireless power. In 1892, just after returning from a European lecture tour, he decided to experiment with long-range power transmission [11]. Actually he had done some very interesting experiments long before then that probably led up to this. One of the earliest experiments that he performed at his lectures with wireless power was to set up two large metal plates about 18 feet apart. On a table between these plates were some of his glass tube lamps. When the plates were connected to a powerful oscillator, the tubes lit up. Tesla first demonstrated this in November of 1890 [12].

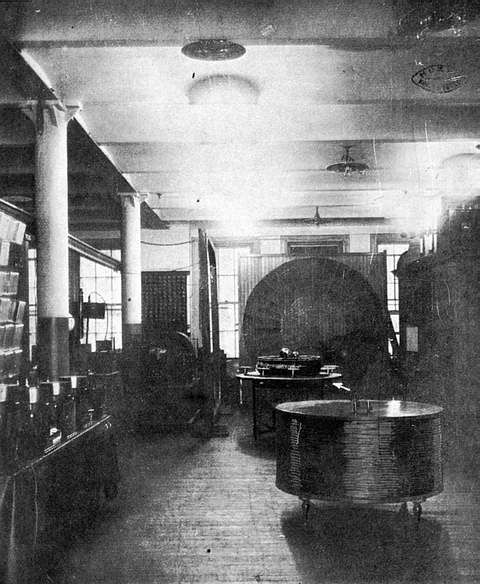

In Tesla's laboratory, a similar effect was demonstrated using dynamic magnetic fields instead of electric fields. Built in 1892, the workshop itself was a room 40 feet wide and 80 feet long, with a 12-foot ceiling. Around this room, Tesla ran a cable that was connected to an oscillator [13]. Secondary coils place in the room would spout sparks when the loop was energized and tuned to their resonant frequency. (See: above) Although these experiments were amazing for that time, they did not offer a means of transmitting power, and Tesla knew it. They were simply induction effects on a very large scale. Tesla's first announcement of a possible plan for wireless broadcasting was made in a lecture delivered before the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia on February of 1893 and before the National Electric Light Association in St. Louis on March of the same year [14]. The lecture was entitled "Light and other High-Frequency Phenomena." In this lecture, a part was included on resonance. Tesla showed that by using a circuit tuned to resonance, and using very high frequency, only a single wire was necessary for carrying power, with no need for a return conductor. In doing this, a light or special radio frequency motor would be connected with one terminal to the oscillator and the other to a large metal plate. After demonstrating this, Tesla suggested that since only one conductor was needed for high frequency, then possibly the earth could be used as that conductor. By learning the resonant frequency of the earth, the transmission of intelligence or even power could be possible.

In the above diagram used in the lecture, an oscillator S is connected to an elevated plate P, which acts as a reservoir of electricity (condenser), and the ground, which would also act as a reservoir. Any electrical disturbance would create an effect or change in potential in the earth, which could be detected within a certain radius. However, what this radius would be is very hard to tell. Tesla had no idea of what the electrical properties of a huge sphere like the earth would be. Tesla suggested the use of a trial and error method of finding the earth's natural period of vibration (if it had one at all). This could be done by using an oscillator of very great power and trying different frequencies to see which one would cause the greatest effect on the surrounding ground. Since the density of the charge would be very small when distributed over the earth, there would not be much loss, and in theory as Tesla stated: "It would not require a great amount of energy to produce a disturbance perceptible at great distances, or even all over the surface of the globe." [15] Tesla later explained the problem of finding the resonant frequency of the earth. What he had to know was whether the earth behaved like a conductor of finite dimension or as an infinite conductor. He believed that the earth would act much like a wire would in carrying radio frequency electric waves. If the earth acted like an infinite conductor, no resonance effects would exist. As in a wire of infinite length, the waves would travel along the wire with no reflection and no build-up of power. If this were the case with the earth, Tesla's transmitter would create local vibrations that would vanish and fade into the distance. However, if the earth acted like a finite conductor, it would have a resonant frequency. The current would travel along the earth until it reached the opposite side and was reflected back. On its way back, the waves would interfere with the oncoming waves and produce interference. If the distance from the transmitter to the opposite side of the earth were equal to one half of the wavelength of the disturbance or any multiple of that, the waves would completely cancel out. If though, the distance is equal to one-quarter wave length or any odd multiple of it, the waves would add together, and a state of resonance would exist. Naturally, Tesla knew that the earth was finite, but it could have acted as an infinite body due to resistance and its curvature, which might have absorbed the waves before they could be reflected. The first step toward discovering these facts was to build an oscillator of sufficient strength to disturb the earth's electrostatic equilibrium. Since Tesla did not keep many notes on his experiments, very little is known about the details of his research. It is known, though, that in the latter part of 1892, he made an important discovery. Up to that time, the disruptive discharge coils bore little resemblance to the well-known Tesla Coils of today. This was because they were built much like regular induction coils, with a multilayered spool for the secondary and the primary wrapped around it. The power and voltage of these devices was limited to the insulation possible with such a configuration. Tesla found that by making a large coil with a single layer of wire on the secondary, extremely high tension could be produced with ease. Tesla called this the Quarter Wave Coil because the length of wire in the secondary coil was about equal to a fourth of the wavelength of the oscillation it produced [16]. The primary coil, which is only a few turns of heavy cable, is at the base of the secondary and very loosely coupled to it. The base of the secondary is grounded and voltage develops at the upper terminal instead of both ends as in earlier coils.

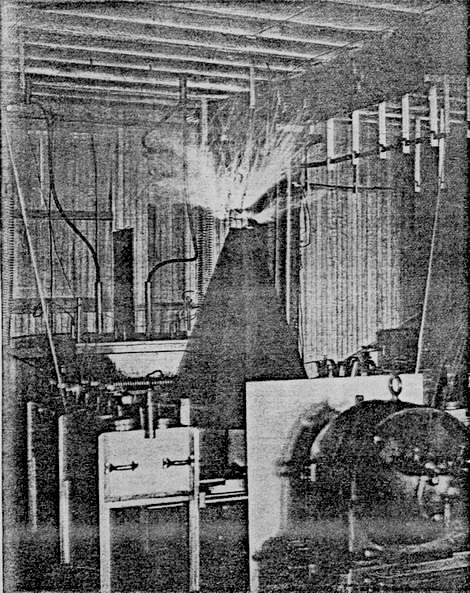

Using a conical coil, Tesla developed 1,000,000 volts in the spring of 1893 [17]. This coil can be seen in the first photograph (above). A transformer of very high voltage powered it. The condenser is a bank of 32 leyden jars, which can be seen to the left and right of the coil in two banks of 16 each [18]. The spark gap can be seen to the left of the coil. This was a "quenched gap" made up of a long row of thick copper disks stacked together with small spaces between for the spark. [DPM - a series gap] Behind the coil is an oscillator of the older type, immersed in a wooden oil tank. An ebonite sheet between the two high-tension terminals prevented corona lose. In 1893, Tesla was involved with Mr. Westinghouse in the design and installation of generators of the polyphase type in a amazing new power plant at Niagara falls [19]. Later in 1894, the Worlds Fair was to be illuminated by alternating current, and both Tesla and Westinghouse were very busy with this [20]. Tesla was given a personal exhibit there, where he demonstrated his AC motors and some of his high frequency discoveries. The Second New York LaboratoryIn 1895, on March 13, Tesla was felled by a great tragedy [21]. The six story building in which his laboratory was located burned down. The fourth floor, where his equipment was, collapsed down to the second floor and all his machinery was destroyed. None of it was insured. His lecture equipment, notes, photographs, and his famous Worlds Fair exhibit were all lost. This, however, was not the greatest loss. Tesla possessed a phenomenal memory and could easily rebuild, and many of his photos were copied.

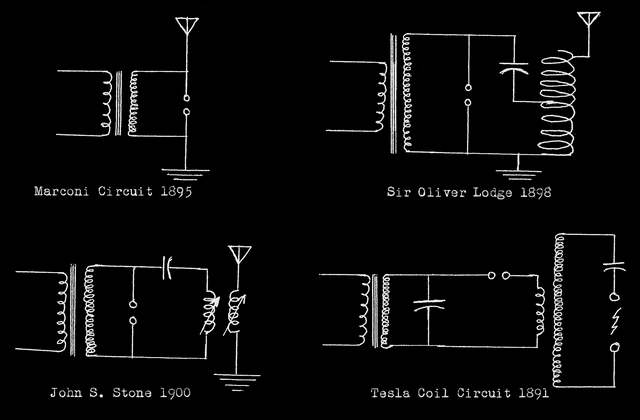

At the time that Tesla's lab burned down, he was developing a wireless transmitter for communications. By 1895, Tesla claimed to have completed this system and was prepared to test the prototype [22]. There is little doubt that Tesla's powerful oscillators could be used for this purpose with success. In that same year, Marconi officially became the first man to send signals without wires [23]. The apparatus that he used was of the most primitive order (above). The highly advanced four circuit tuned system used by Tesla was not patented for radio used until 1900 [24]. At the time of the fire, Tesla was at the height of his scientific fame. A number of people contributed money to him, and he himself was by no means poor. Four months after the fire, in July of 1895, he took up residence at 46 E. Houston Street on the top floor, and began to reconstruct his laboratory [25]. He Spent the next year or so rebuilding the equipment he was using in his first lab. The second lab was illuminated entirely by fluorescent lighting, some of which was wirelessly powered. Tesla, who had a flair for the dramatic, would often close the heavy shutters during the day and show visitors the eerie moonlike glow produced by these lamps. From 1896 though 1897, Tesla carried on work in several lines of research, including mechanical oscillators and solar power engines [26]. However, his primary fascination was still with high frequency current. To investigate wireless power further, Tesla wanted to study the effects of voltages beyond the one million volts produced by his conical coil. He had not yet detected any earth resonance effects. By building bigger and bigger coils, Tesla knew that he could reach any desired potentials, but he felt that there should be a better way that would not require bulky coils or cumbersome insulation. In other words, he wanted to make a relatively small transformer that would be able to deliver almost any voltage.

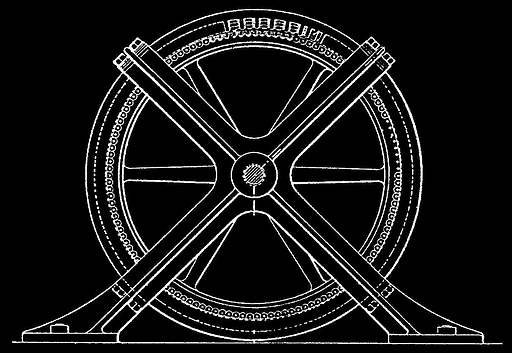

Tesla found the solution while experimenting with variously shaped quarter wave coils. He found that when a flat spiral shaped secondary is used, there is an absence of corona loss and shorting between turns [27]. Even when bare wire was used, there was no difficulty in producing many millions of volts. This type of coil can be seen in the photograph of the second laboratory (above). The primary and secondary coils were both mounted on a wooden base and could be pivoted to bring the coil into a horizontal position. The oscillator on his main spiral coil was powered by a 50,000-volt transform, which charged a 0.04-microfarad condenser [28]. This was discharged though the eight foot (244 cm) primary, which was a single turn of heavy stranded wire; by means of a high speed mechanical break (replacing the spark gap used in earlier coils). This rotary break closed the circuit 5000 times per second. The inductance of the primary coil was 8 micro henries, and the total inductance of the primary circuit was 10 mh. The frequency used on this coil varied from 230 KHz to 250 KHz. The secondary coil was made up of one hundred turns of insulated #8 copper wire. The turns began at the primary coil and were carefully spaced to reduce destructive capacitance in the coil, which will reduce the voltage and cause power loss. The outer rim of the secondary would be grounded or possibly connected to the primary. The center of the coil was connected to a bar, which stuck out and curved down slightly. A six-inch ball was sometimes fastened to the end of the bar. The maximum voltage of this coil was two and one-half to three million volts, which created discharges up to 16 feet in length. (The conical coil had produced up to 6-foot arcs). A large variety of experiments were carried on with this device. One of Tesla's favorite demonstrations, to show that high frequency current was not harmful, was to stand on a platform connected to the oscillator and instruct his assistants to raise the potential to nearly 3 million volts [29]. At that voltage, he was covered with sparks and said that he felt as though he were burning up. One of the most important discoveries that Tesla made was the effect that very high voltage had on the air's insulating properties [30]. Normally, air becomes a fair conductor at about 75 millibars, but Tesla found that with high frequencies and very high voltage, air becomes conducting at much higher pressure. Using the three million volt spiral coil, Tesla tested the feasibility of using the air to conduct power. He connected a 50-foot to be containing air at a pressure of 120-150 millibars to the central terminal of the coil [31]. The other end of the tube was connected to the center of a similar coil that would act as a step-down transformer. With this arrangement, electric power could be transmitted with good efficiency. At three million volts, even air at normal pressure could conduct some electricity. This led Tesla to believe that he had discovered a way to transmitting not just signals, but usable amounts of power. By using the atmosphere for one conductor and the ground for the other, power in quantities large enough for industrial purposes would be made available to anyone. This would, at first, have been used for illuminating isolated homes or other places where it was not practical to supply electricity. Tesla proposed building towers from which balloons would be flown. The current at a voltage of 20-50 million volts would be cabled up to 30 or 35 thousand feet where the air is adequately rarefied [32]. Tesla had not tested voltages nearly this high, so he suggested that it may be possible to use a much lower altitude for the transmission. At 20 million volts, it would not require much amperage to yield a great amount of wattage, but it should not be immediately assumed that this system would really work. In the spring of 1897, Tesla began distance testing of his wireless telegraphy system (not to be confused with the aerial power system) [33]. On a boat in the Hudson river, he placed a receiver and was able to pick up signals at a distance of 25 miles. This was not the greatest range of the system, but it was as far as the boat could go. He announced the completion of this invention in July of 1897 [34]. Tesla made no attempt to patent this until several years later, after he had done extensive research on it. He did patent his aerial power system in 1897 (No. 645,576 and 649,621. Not granted until 1900) [35]. The range of 25 miles was a considerable improvement over Marconi's equipment, which had a range of two to nine miles at that time [36]. The oscillator was powerful enough to send signals to very great distances, but unfortunately, Tesla was not using long vertical antennas at that time. He was working on the principle that his signals were traveling through the earth as electric waves.

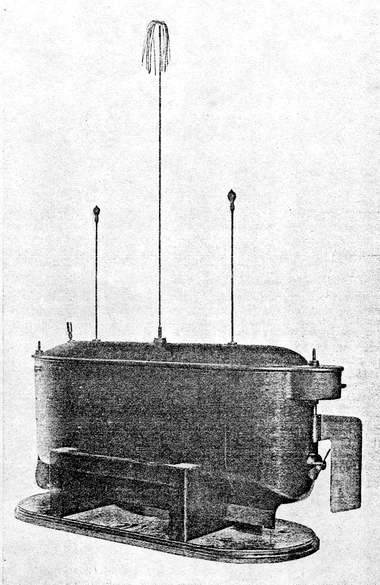

In September of 1898, Tesla demonstrated a remote controlled boat in Madison Square Garden during the First Annual Electrical Exhibition [37]. This boat is shown above. It was controlled by means of a single tuned circuit that caused it to change direction. It could be made to steer in different directions and stop and start with signals transmitted from a small oscillator near the edge of the huge tank the boat sailed in. Tesla called this machine an Automaton, and he believed that it would one day be used to fight wars. Tesla suggested that boats and flying machines could be filled with explosives and then directed to their targets for detonation. It was patented in November of 1898 (No. 613,809) [38]. At that time, Tesla exhibited a larger boat containing several tuned circuits that could respond to signals sent at different frequencies. This boat employed wire loops within its hull that had condensers in them to cause them to resonate. There was no outside antenna. This vessel could stop, start, turn and light lamps mounted on it. Tesla was advised not to attempt to patent this type of system by his patent attorney. This may have happened because Sir Oliver Lodge had patented a method of tuning wireless telegraph circuits earlier that year [39]. Notes for Part I1. John J. O'Neill, Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla New York, Ives Washburn Inc., 1944, pp 9, 277. 2. Ibid. P. 86. 3. "Tesla's Laboratory Burned", Electrical Review (of New York), March 20, 1895, p 145. 4. O'Neill, Op. Cit., p 86. 5, Ibid., p. 87. 6. "Electromagnetic Waves", Encyclopedia Britannica 1970, VIII, p 233. 7. "Radiation: Biological Effects", Encyclopedia Britannica 1970, XVIII, p 1033. 8. Thomas Commerford Martin, The Inventions Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla, Second Edition, New York, Press of Milroy & Emmet, 1894, p 381. 9. O'Neill, Op. Cit., p 91. 10. Ibid., pp 102, 121. 11. Nikola Tesla, "My Inventions: 5. The Magnifying Transmitter", Electrical Experimenter, June 1919, p 173. 12. Ibid., p 148. 13. Thomas Commerford Martin, "Tesla's Oscillator and Other Inventions", Century, April 1895, pp 926-927. 14. O'Niell, Op. Cit., pp 130, 131. 15. Ibid., p 133. 16. Patent No. 645,576, "System of Transmission of Electrical Energy", March 20, 1900, p 3. 17. Nikola Tesla, "My Inventions: 5. The Magnifying Transmitter", Electrical Experimenter, June 1919, p 173. 18. Samuel Cohen, "Mr. Nikola Tesla and His Achievements", Electrical Experimenter, February 1917, p 713. 19. O'Niell, Op. Cit., p 105. 20. Ibid., pp 102-103. 21. "Tesla's Laboratory Burned", Electrical Review (of New York), March 20, 1895, p 145. 22. O'Niell, Op. Cit., p 123. 23. "Radio", Encyclopedia Britannica, 1970, XVIII, 1038. 24. Ibid., 1039. 25. O'Niell, Op. Cit., p 123. 26. "The New York Wizard of the West", Pearson's Magazine (London), May, 1899, pp 470-476, and O'Niell, Op. Cit., pp 155-165. 27. Nikola Tesla, "My Inventions: 5. The Magnifying Transmitter", Electrical Experimenter, June 1919, pp 173, 176. 28. Patent No. 645,576, "System of Transmission of Electrical Energy", March 20, 1900, pp 3-4. 29. Kenneth M. Swezey, "Experiments with Tesla Resonator", The Experimenter, July 1925, p 625. 30. O'Niell, Op. Cit., p 142. 31. Patent No. 645,576, "System of Transmission of Electrical Energy", March 20, 1900, p 4. 32. Ibid., pp 4-5. 33. O'Niell, Op. Cit., p 126. 34. Ibid., pp 125, 126. 35. Patent No. 645,576, "System of Transmission of Electrical Energy", March 20, 1900, p 1 and Patent No. 649,621, "Apparatus for Transmission of Electrical Energy", May 15, p 1. 36. "Radio", Encyclopedia Britannica, 1970, XVIII, 1038. 37. O'Niell, Op. Cit., p 175. 38. "Tesla's Wireless Boat", Scientific American, November 19, 1898, p 326. 39. "Radio", Encyclopedia Britannica, 1970, XVIII, 1039. |