Nikola Tesla's Investigation of High Frequency Phenomena and Radio Communication (Part III)Donald Mitchell Pelican Rapids, Minnesota, 1972

The World Broadcast SystemWhen Tesla's work in Colorado was completed, he returned to New York in mid January of 1900 [58]. He immediately applied for a patent on the wireless telegraphy system that he had been perfecting in Colorado; however, the patent was not granted until 1905 [59]. This patent described the stationary wave theory and stated that three conditions had to be met before the system would work. First, the frequency had to be such that the diameter of the earth would be an odd multiple of the quarter wavelength of that frequency. Tesla believed that the current for the transmitter traveled directly through the center of the earth, but more likely, it travels around the circumference. If this were so, then the distance from pole to pole along the surface of the earth would have to be used instead of the diameter, for calculating the frequency. The second condition was that the frequency should, for ideal results, not exceed 20 KHz, or radiation loss would impair the action of the transmitter. The third condition was that the wave train of the oscillator must last at least 1/12 of a second. That is the time that it took for the signal to go to the other side of the earth and return.Along with this, the patent also contains a receiving circuit that uses a synchronous rotary rectifier to detect signals. This circuit bears close resemblance to the "tickers" or tone wheels used a few years later with the Poulson Arc transmitters. In the tone wheel, a rapidly spinning wheel interrupts the radio signal from the antenna and heterodynes with it to produce a shrill whistle that could be heard easily with headphones. Tesla's device would be for lower frequencies so he planned to have it more carefully synchronized to produce almost pure direct current. For the detection of signals that were too faint for headphones, Tesla proposed using a device he had invented in 1891 to respond to the direct current from the rectifier. This device consisted of an evacuated glass bulb with an electrode in the center. When this was connected to a high voltage transformer powered by an alternator (of high frequency), an electron "brush" was formed. This brush was so sensitive to electric and magnetic fields that a one-inch horseshoe magnet at six feet would cause it to be deflected. After succeeding in sending signals 600 miles in Colorado, Tesla felt that his long wave system was ready for full scale use. He set out immediately to design and build a giant Magnifying Transmitter on Long Island that would be able to send signals across the Atlantic to England. Beyond just replacing the underwater telegraph cables, Tesla conceived of a much more ambitious plan. Up to that time, most scientists were only interested in using radio for point-to-point transmission. Tesla, however, saw that wide range broadcasting was possible. Tesla was not sure if a single transmitter could be picked up all over the world (he had not tested his vacuum bulbs yet), so he suggested that a global network of relay stations might be required. He called this idea the "World System" and in 1902, he published an article explaining some of the points of the plan. This was printed during the construction of the transmitter.

Tesla did not want to build a separate Magnifying Transmitter for each frequency (at least not for telegraphy transmission), so he developed a way for one transmitter to send signals on many frequencies at the same time, thus creating a wave complex. Naturally it is not easy to make a circuit oscillate at different frequencies, but Tesla invented a means of allowing the transmitter to send impulses in a rapid succession of changing frequencies. This would have been done with a complex system of rotary breaks and tuning coils. This could still be used in the double circuit system just described because the impulses would be separated by an insignificant amount of time (thousand of pulses per second would probably have been used). It would be logical to assume that at least three or four frequencies could be sent in this manner by one station, and as many as ten might have been possible. As far as the secret transmissions that Tesla spoke of, we can only speculate. It would not have been difficult to send two meaningless sounding signals in which those impulses common to both signals contain the message. It is indeed unfortunate that more is not known about Tesla's plans. He was a very great thinker, and he was hard at work to develop wireless to its highest potential.

The Shoreham TransmitterIn the fall of 1900, Tesla received $150,000 from J.P. Morgan to build his transmitting station [62]. Along with $50,000 from other wealthy friends, Tesla began work on the construction of an oscillator of incredible size and power.

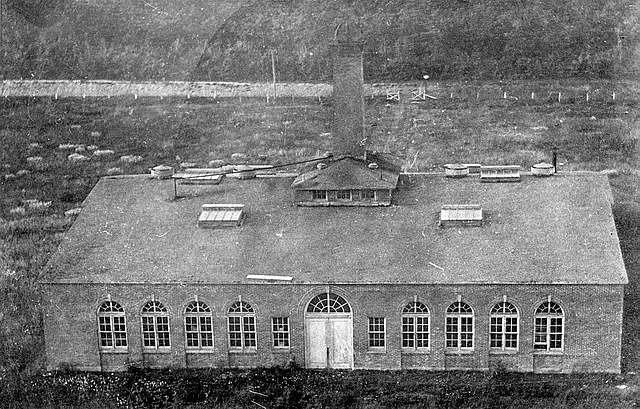

On March 21 of 1901, Tesla arranged for the Westinghouse Electric Company in Pittsburgh to make the transformers and generators that he needed to power the oscillator [63]. During the entire project, Tesla worked closely with the engineers at Westinghouse Co. in designing apparatus. He had chosen a site on Long Island near the city of Shoreham for the transmitter. 200 acres of land were bought from James Warden, the manager and director of the Suffolk County Land Company (This area near Shoreham was then called Wardenclyffe). Twenty acres of the wooded property were cleared for building, and Tesla hoped to purchase an additional 2000 acres in the future of the "Radio City" which he hoped to start there [64]. Tesla employed about fifty people in this new project, including guards to keep people away from the area. Tesla feared that someone might steal some of his inventions (many of which he never patented), and he wished to keep things quiet until he was finished. The famed architect, Stanford White, who was a personal friend of Tesla's, designed a laboratory building (seen above) that would house the power plant and oscillator [65]. Five or six other buildings were to be built later on. Tesla may have planned to build a number of transmitters at that site as his company expanded.

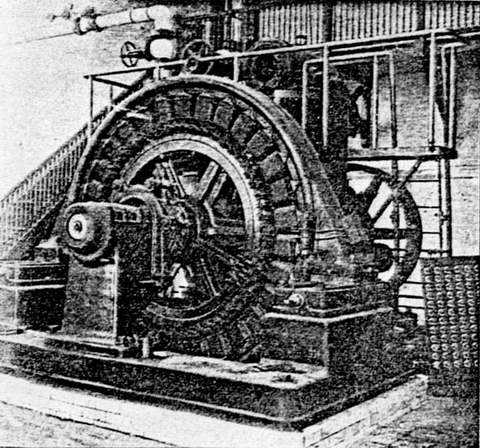

The laboratory was a brick building about 100 feet square and as tall as a two-story building. It was completed in a few months, and the concrete footings for a huge tower were laid 250 feet south of the building. Tesla had ordered a couple of 100 horsepower steam engines and they were installed in the power plant in November of 1901. A 300-kilowatt Westinghouse Alternator (above) was installed later. The laboratory building was divided into four parts: the boiler room, the engine and dynamo room, a workshop containing eight metal lathes, and a laboratory. The building also houses offices and a small library. The oscillator, for what would have been the largest Tesla Coil ever built, was contained in the building and would be connected to the primary of the Magnifying Transmitter by underground cable [66]. Four seven-foot high steel tanks filled with oil were to contain the high voltage transformer. Seven more tanks would house the condenser bank, and one special tank was to be filled with a system of coils and regulating apparatus for controlling the frequency and power of the oscillations. Not all of this equipment was installed, but even when not finished, the inside of the lab was an impressive sight. Its huge tanks and giant pieces of machinery made contemporary efforts at wireless transmission seem very pitiful. In December of 1901, Marconi made history by transmitting the letter "S" across the Atlantic [67]. The equipment that he used was a crude single circuit transmitter (as opposed to Tesla's primary-secondary type) contained in a small building and operated by a heavy wooden lever. Although Marconi's achievement was great, Tesla was far ahead of him. Some of Tesla's agents were already searching for a suitable area in Britain for a major receiver and relay station. In June of 1902, Tesla moved out of his laboratory on Houston Street and into the Wardenclyffe building [68]. The laboratory section was soon filled with lecture equipment, coils, X-ray machinery and other devices. In the workshop, glass blowers were busy making the electron bulbs that Tesla hoped to use in his receivers.

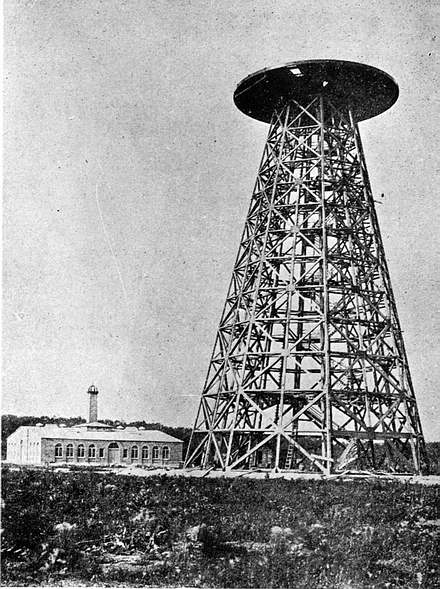

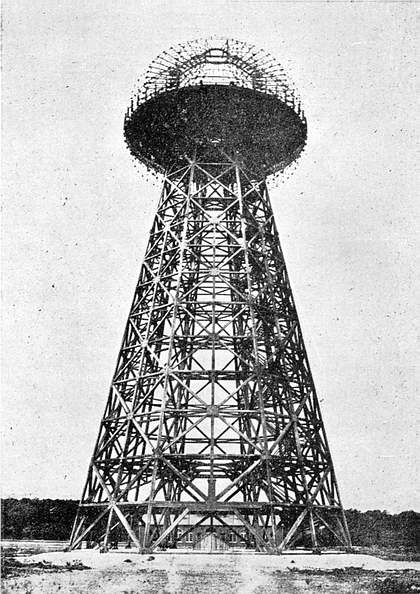

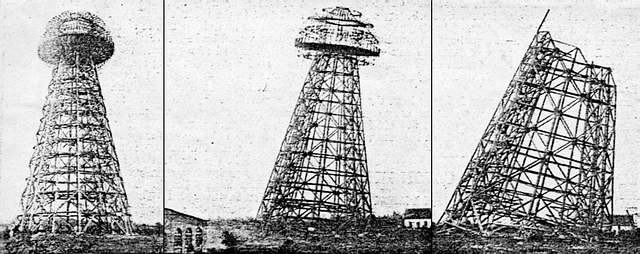

The most striking object at this site was the strange tower that was being constructed there (above). This was to be the actual Tesla Coil or Magnifying Transmitter. The tower was made out of large wooden beams joined together with copper gussets and bronze bolts. No ferrous metals were used anywhere in the structure because of magnetic hysteresis which would cause heating and power loss. The sections were constructed on the ground and later hoisted into place with cranes. When completed, it was a pyramid shaped tower having eight sides. The smallest dimension across he base was 95 feet, and it stood 154 feet high [69].

By the early part of 1903, a 55 ton copper mesh dome was placed on the top of the tower. This dome was 66 feet in diameter and was to have been covered with copper sheeting to form a giant copper electrode elevated above the ground by the insulating wooden tower. With dome, the tower stood 187 feet tall (above). Beneath the tower a copper pipe was driven 150 feet into the ground to make a good earth connection. Local rumors told that pits and underground tunnels were being constructed, but these do not appear to be true. Years later, there was reported to be well 12 feet wide and 100 feet deep at the site of the tower.

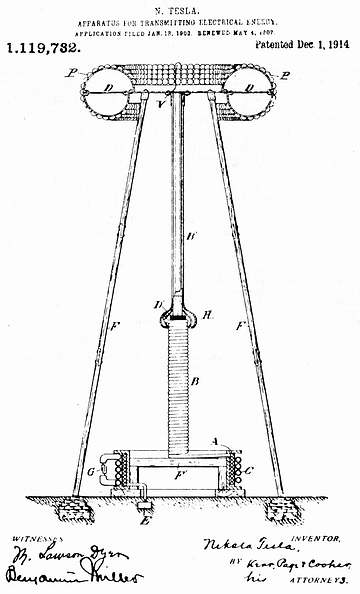

The exact plan of the Magnifying Transmitter is not known because it was never finished. However, from what is contained in interviews with Tesla for newspapers, it is known that it would have resembled diagrams in one of Tesla's patents (No. 1,119,732). This patent (above) deals mainly with methods of handling very high voltage. In the diagram, "C" is the primary coil of a Magnifying Transmitter. "G" is the oscillator, "A" and "B" are two sections of the secondary coil, and "D" is the elevated terminal, a torus shaped electrode, in this case. The bumps on the terminal ("P") are to prevent the freely resonating circuit from getting out of hand. If the voltage gets too high, it would arc from one of these bumps instead of some part of the circuit nearer the ground. With energy that would have dwarfed the Colorado transmitter, this station could destroy itself by such an accident. The reasons for not completing the Wardenclyffe station were numerous. In the fall of 1903, J.P. Morgan withdrew his support of the project and a number of other financiers quickly followed him [71]. Tesla was sued several times from Colorado Springs for unpaid bills and even had to appear in court out there on September 6 of 1905 [72]. To get money, Tesla ordered the Colorado Springs lab sold, and in 1906 some of his equipment was put up for auction there. To top all this off, Tesla's AC motor patents in Europe expired and left him without any income from royalties. In 1905, Tesla had set up a temporary factory in the Wardenclyffe building and began to manufacture Tesla Coils for medical and industrial use [73]. He also invented a new type of turbine that operated without blades [74]. This machine worked very well, but no one seemed interested in it. In spire of all the financial troubles Tesla had, it may have been his health that forced him to abandon the Wardenclyffe building in 1906. He had suffered from several serious nervous breakdowns brought about from over work (Tesla slept about five hours a night and the rest of the day was filled with work) during the past two decades before then. Local people reported seeing Tesla collapse from exhaustion while taking a walk by the sea.

In 1912, Westinghouse removed their equipment, which had not been paid for, and in 1915 Tesla was forced to turn over the mortgages to the property to Waldorf Astoria [75]. In July of 1917, they had the tower torn down and sold for scrap. The building was sold in 1938 to Peerless Photos Products Inc. who transformed it into a factory for making light sensitive paper [76]. After leaving Wardenclyffe, Tesla opened up an office at 165 Broadway in New York [77]. By this time, Tesla did not have enough money to carry on much research, and he became more and more of a recluse. In 1915, he became involved in a law suite with Marconi [78]. Tesla claimed that Marconi's patents were in violation of his own patents No. 645,576 and 649,621. Tesla lost this sit, but in 1943, Marconi's key patents were invalidated by the Supreme Court [79]. In the years after Wardenclyffe, Tesla wrote a number of articles in which some of the details of his earlier experiments were revealed. Many facts about Tesla's work may never be known, however. His laboratory in Colorado Springs was destroyed so completely that today no one seems to know the exact place where it was located (the city of Colorado Springs expanded out over the area). On May 23, 1966, an historical marker was placed near the site [80]. The detailed plans for Tesla's fabulous Wardenclyffe broadcasting plant appear to be lost (Peerless Photos has made an extensive search for the plans, but the building firms, libraries and historical societies in that area have no idea what became of them). Tesla's greatest misfortune seems to be that he was twenty years ahead of his time. Few people understood Tesla's ideas, and Tesla did not go to great lengths to make them clear. It is indeed ironic that only two miles from Tesla's lost Wardenclyffe plant, the Radio Corporation of America years later established at Rocky Point, one of the most powerful broadcasting stations in the world [81].

AcknowledgementsSpecial thanks to Mr. Vernon Goodin and the Moorhead Public Library (Moorhead MN) for assistance in obtaining articles. Thanks also to Carleton College Library, Cleveland Public Library, Macalister College Library, North Dakota State University Library (Fargo ND), Penrose Public Library (Colorado Springs, CO), University of Iowa Library (Ames, Iowa), University of Minnesota Library (Minneapolis), University of North Dakota Library (Grand Forks), and the University of Wisconsin Library (Madison). My thanks to the following organizations for their cooperation and help: The Carnegie Institution of Washington, The New York Historical Society, The Smithsonian Institution (Washing ton DC), The Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities (Setauket, LI), and Peerless Photo Products Inc. (Shoreham, LI). Special thanks to Mr. Leland I. Anderson of Denver CO for his assistance. Thanks to Mr. Jeff Hohman of Pelican Rapids MN, Mr. George Martin of Cormorant MN, and Mrs. Rosemary Hetzler of Colorado Springs CO for their help in obtaining articles on Tesla. For their helpful information on Tesla, my thanks to Mr. Thomas R. Bayles of Middle Island, LI, Mr. Harry Goldman of Glen Falls NY, and Mr. E. J. Quinby of Summit NJ. My thanks also to Mrs. Maryann Franklin and Mr. Richard Macgregor of Pelican Rapids MN for assistance in putting this report in proper form.

Notes for Part III58. Leland I. Anderson, "Wardenclyffe--A Forfeited Dream", Long Island Forum, August 1968, p 146. 59. Patent NO. 787,412, "Transmitting Electrical Energy Through the Natural Mediums", April 18, 1905, p 1. 60. John J. O'Neill, Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla New York, Ives Washburn Inc., 1944, p 203. 61. "The New York Wizard of the West", Pearson's Magazine (London), May 1899, p 475. 62. O' Neill, Op. Cit., pp 210-211. 63. New York Tribune, March 22, 1901, 6:6. 64. "Mr. Tesla at Wardenclyffe, Long Island", Electrical Worlds, September 28, 1901, pp 509-510. and "A New Tesla Laboratory on Long Island", Electrical Worlds, September 27 1902, pp 499-500. 65. O' Neill, Op. Cit., p 204. 66. Brooklyn Eagle, April 24, 1939, p 1. 67. I.O. Evans, Inventors of the World London, Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd., 1962, pp 140-141. 68. Leland I. Anderson, Op. Cit., p 148. 69. Nikola Tesla, "Transmission of Electrical Energy Without Wires", Scientific American, June 4 1904, supplement. 70. Ibid., supplement. 71. O' Neill, Op. Cit., p 198. 72. Colorado Springs Gazette, September 6, 1905, p 5. 73. Leland I. Anderson, "Wardenclyffe--A Forfeited Dream (part 2)", Long Island Forum, September 1968, p 169. 74. Ibid, p 170 and O' Neill, Op. Cit., pp 218-228. 75. Anderson, Op. Cit., p 171. 76. Ibid., p 172. 77. O' Neill, Op. Cit., p 214. 78. "Tesla Sues Marconi on Wireless Patent", Electrical Review, August 14, 1915, p 297. 79. Leland I. Anderson, "Nikola Tesla", Collier's Encyclopedia, 1964, XXII, p 181. 80. Free Press, Colorado Springs, Colo., May 24, 1966, p 20. 81. The Sunday Review (New York), March 18, 1962, p 10. |