|

The last Soviet missions to Venus arrived in 1985: the twin spacecrafts Vega-1 and Vega-2.

This is the final chapter in a program of Russian exploration, which discovered most of what we know today about our neighboring planet.

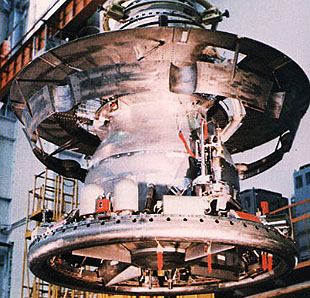

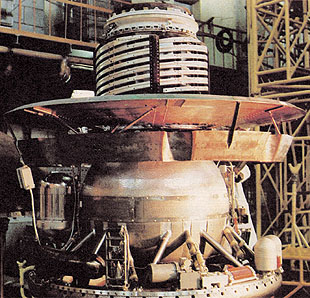

For the 1986 return of Halley's comet, Russian astronomer V.G. Kurt proposed a multipurpose mission to visit Venus and then rendezvous with the comet. With orbital mechanics expert A.A. Sukhanov, he proved the plan's feasibility, and it was accepted. The 5-ton vehicle is seen above., the 2.4 meter spherical heat shield contained a Venus lander and a balloon-born aerostat. The cylindrical central core holds fuel and the course-correction engine, and around the base is a pressurized toroidal compartment for spacecraft electronics. The temperature control radiator can be seen on the back, and large helical antennas for lander telemetry reception would be mounted to either side (where black disks are seen). The cameras and spectrometers for Halley's comet are mounted on an extended platform, seen on the lower right. Metal dust shields and thermal insulation blanketing are absent in this public display model. R.Z. Sagdeev, head of the Space Research Institute (IKI) managed the mission with the Interkosmos Committee, a group of East European scientists who shared in the construction of scientific instruments. Participating nations included Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, France, East Germany, West Germany, Hungary, Italy and Poland. International cooperation, including the joint use of Soviet and American deep space networks. The name "Vega" is an abbreviation of the Russian "Venera-Gallei".

The Launch of Vega-1 Vega-1 was launched on December 15, 1984, and Vega-2 followed on December 21. Seen above, the Proton rocket is powered by a kiloton of unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide. A colorless liquid, N2O4 converts into orange nitrogen dioxide gas, resulting in the colorful but poisonous plumes of smoke during engine startup. First lifted into a parking orbit, the fourth stage engine ("block-D") accelerated the spacecrafts to escape velocity, on trajectories to the planet Venus. The Vega LandersVega-1 arrived at Venus on June 11, 1985, releasing the descent vehicle and relaying telemetry to Earth as it flew past the planet. Atmospheric entry is a rough ride, with 210 gravities of overload during the sudden deceleration from 11 km/sec to the speed of sound. A series of supersonic and subsonic parachutes reduced the speed further, and after a ten-minute descent in the clouds, the main parachute was detached and the lander fell freely, slowed only by aerodynamic braking. After an hour-long descent, surface contact was made at 8.10°N 175.85°E. The 750 kg lander transmitted experimental data from the surface for about 20 minutes, in conditions of 95 atm pressure and 467°C.Vega-2 arrived on June 15, and following a similar plan, it landed at 7.14°S 177.67°E. At a slightly higher elevation, the pressure at this site was 91 atm, with a temperature of 461°C. The vehicles landed about 1300 km apart, near the equatorial plateau of Aphrodite Terra.

The Vega landers were a continuation of the highly successful design used since Venera-9. A few aerodynamic modifications were made to increase the stability of the lander during free fall. Damping blades can be seen underneath the vehicle, to prevent spinning, and a sleeve just below the aerobrake reduces the turbulent effect of externally mounted instruments. In the picture on the left, we can see the small twin bell-shaped compartments of the VM-4 hygrometer, the pressure/temperature/pressure sensor unit, and the soil drill. In the picture on the right, the large shiny bell-shaped compartment of the SIGMA-3 gas chromatograph is just to the left of the pressure hull. Next is the dark sausage-shaped vacuum reservoir of the soil-drilling device, the Prop-V penetrometer, some unidentified instruments, and again the VM-4 hygrometer. A complete list of experiments on the lander is given in the following table:

Cameras and solar spectrometers are absent from these missions, since the Vega landings were on the night side of Venus. Traditional experiments included the soil drill, gamma-ray spectrometer and soil penetrometer. New experiments focused on answering open questions about the nature of the Venusian cloud aerosol.

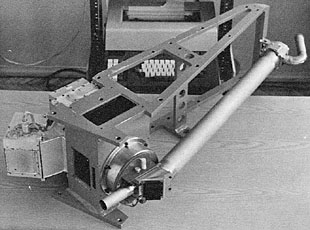

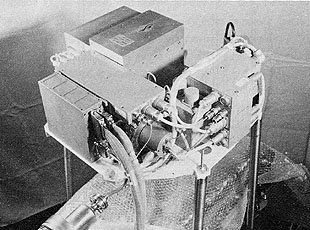

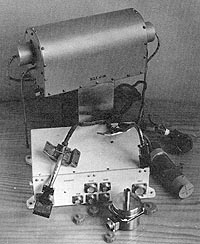

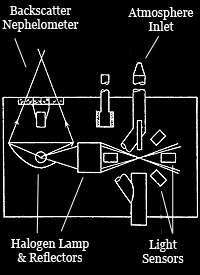

To the naked eye, Venus is nearly featureless and colorless; however, dramatic patterns of cloud circulation are seen in the ultraviolet. The chemical responsible for UV absorption is a mystery, which the ISAV-S active spectrometer attempted to solve. Passing atmosphere through an external 85 cm tube, light from a xenon lamp traversed the gas. The absorption spectrum from 230-400 nanometers was measured at 512 points, and both landers returned about 30 full spectra from 55 km to the surface. The Spectrometer and electronics (units S and E) are mounted inside the spherical pressure hull, where the cycloramic camera was housed on the Venera landers. The pipe that the atmosphere flows through (unit K) is outside, extending down to the landing ring. The photo above shows all three units. Results showed the presence of sulphur dioxide and possibly elemental sulphur vapor, both important UV absorbers. By the time the lander reached 10 km altitude, the UV was completely absorbed, mostly because of material coating the surfaces. For a time, scientists were satisfied that the clouds of Venus simply consisted of an aerosol of sulphuric acid droplets. The scattering experiment on Venera-9 hinted at more complex structure; and in 1978, Venera-12 and the American Pioneer large probe completely shattered this simple picture. Venera-12 discovered substantial amounts of chlorine in the cloud droplets, as well as traces of iron. And the Pioneer probe's particle-size spectrometer discovered three distinct population peaks of particle sizes, a tri-modal distribution. In addition to the expected droplet sizes of the sulphuric-acid theory, groups of smaller and larger particles were observed. A controversial theory was proposed that the large "mode-3" particles were crystals, not spherical droplets. To address these questions about the aerosol composition, a battery of new experiments were designed. The MALAKHIT mass spectrometer collected cloud particles, segregating them inertially, and trapping heavy and light particles in two filters. The material was then vaporized at high temperature and introduced into a hyperbolic mass analyzer. In the heavy particle sample, sulphur trioxide was found (sulphuric acid anhydride), as well as smaller amounts of chlorine. Unfortunately, only the spectrometer on Vega-1 functioned.

Venera-12, 13 and 14 contained the SIGMA and SIGMA-2 gas chromatography experiments, to analyze the atmosphere. For Vega, the SIGMA-3 was designed to measure the amount of suphuric acid, by trapping cloud droplets in a filter and performing a chemical reaction to produce identifiable gas products. Although there was little doubt of its existence, MALAKHIT and SIGMA-3 were the first experiments to directly detect sulphuric acid in situ. With improved accuracy, temperature and pressure were measured during the descent. The unit contained two platinum-wire thermometers, and three highly accurate pressure sensors, calibrated for 0-2, 0-20 and 2-110 atmospheres. Unfortunately, the unit on Vega-1 malfunctioned. An improved hygrometer was included to measure water vapor. Venus is a very dry planet, but water vapor plays a critical role in the chemistry of its atmosphere, being necessary for the formation of the cloud aerosol of sulpuric and phosphoric acid. Two experiments studied the size distribution of aerosol particles. Both ISAV-A and the LSA experiment passed a minute stream of atmosphere through a region of strongly focused light. The scattering of light off individual aerosol droplets. ISAV-A measured the intensity of reflection in four directions, and the LSA used a photomultiplier and 256-channel pulse-height analyzer to measure the temporal profile of particles as they pass by. The ISAV-A unit also housed a backscatter nephelometer, which looked out into the atmosphere through a window to measure cloud density. It shared some of the electronic systems with the UV spectrometer, forming the overall ISAV The clouds were found to have the three layer structure first seen by Venera-9, although the lower boundary was less distinct and extended to a lower level. Venera-8 saw a similar effect, which may be typical of the night-time atmosphere. A bi-modal distribution of aerosol particle sizes were found, but no large "mode-3" population. The small mode-1 particles are thought by some to be solid grains of aluminum chloride and ferric chloride, both of which exist as gases in the hot lower atmosphere. ISAV-A data showed that the mode-2 droplets were spherical and 80% of them had a refractive index of 1.4, that of sulphuric acid. The other 20% had an index of 1.7 and may be condensed sulphur.

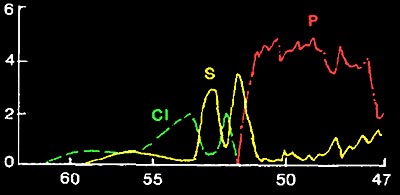

Chlorine, Sulphur and Phosphorus at Various Altitudes X-ray fluorescence spectrometer has been an interesting and important source of data about cloud aerosol composition. Surkov's team at the Vernadsky Institute made significant improvements in the accuracy of the Vega instrument. Chlorine, sulphur and phosphorus were found in significant amounts in the clouds from 63 to 47 km. And again, iron was detected, probably in the form of ferric chloride. It is widely agreed that the upper clouds, of sulphuric acid droplets, result from photochemical reactions in the upper atmosphere. Vladimir Krasnopolsky has proposed a thermodynamically consistent theory in which sulphuric acid begins to decompose down in hotter elevations, and the resulting water molecules combine with phosphorus oxide to form the lower cloud aerosol of phosphoric acid solution. At 18 km, mysterious electrical impulses in systems and fluctuations in Doppler tracking occurred. At the same time, a spike in absorption was recorded by the IVAS-S, probably caused by deposited cloud material being jarred loose. The shock to Vega-1 drove it upwards at 30 meters/sec (70 mph), triggering the post-touchdown program, and thus causing the failure of the soil drill experiment. Venera-11 to 14 reported similar electrical disturbances at altitudes of 12 to 18 km, and all four of the American Pioneer probes experienced electrical damage in this altitude range, knocking out their temperature and photometer sensors at about 12 km. The cause of this "shock layer" in the lower Venusian atmosphere is unknown.

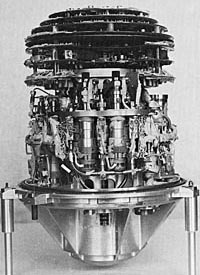

The Vega landers carried both of Surkov's radiological experiments to analyze the crust of Venus. One of the most remarkable engineering achievements on the Venus landers was the soil drill and X-ray fluorescence analyzer. So extreme are conditions on Venus, the soil drill was designed to function only after the thermal expansion of its parts at 500°C. Boring into the soil, a sample was transferred through an airlock into a chamber within the pressure hull. There it was irradiated to excite characteristic X-ray fluorescent emissions. The second experiment was the gamma-ray spectrometer. Using a scintillation counter, it measured the energy spectrum of gamma rays from the three naturally-occurring radioactive elements: Potassium, Uranium and Thorium. To gather the sparse radiation, the device contained a large 63 × 100 mm cesium iodide crystal and an FEU-118 photomultiplier tube, in addition to amplifiers and a 128-channel pulse-height analyzer.

The X-ray fluorescence analyzer provided detailed analysis of the crust of Venus at three sites, including the Vega-2 location. Rocks like basalt are mixtures of complex metal silicates, and the chemical makeup is traditionally expressed as proportions of oxides, as shown above.

The gamma-ray spectrometer functioned perfectly on all five deployments. From the results of both types of analyzers, the crust appears to be a variety of volcanic basalts, except at the Venera-8 site, where readings were more similar to granite. The Vega AerostatsFor some time, French and Soviet scientists had considered the use of balloons to study the Venusian atmosphere. In the 1960s, Jacques Blamont proposed sending a cluster of small balloon probes to Venus. In 1974, a joint French/Soviet mission was discussed that included a Venus orbiter and telemetry relay station, with large balloon probes.At the Space Research Institute, G.M. Moskalenko and V.S. Troshin worked out details of the mechanics of flight in the Venusian atmosphere for a variety of vehicles, and in particular on the system of pressure regulation in balloons. French participation in the Soviet space program was sometimes frustrated by ill-timed strikes, student protests and shifting Franco-Soviet relations. Ultimately, the 1978 balloon plan was deleted from Venera-11 & 12.

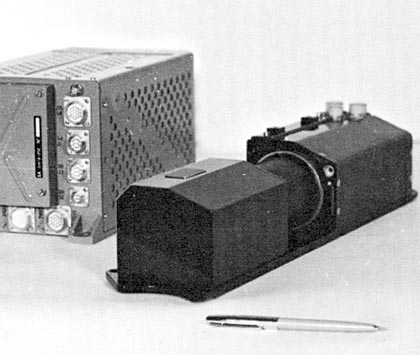

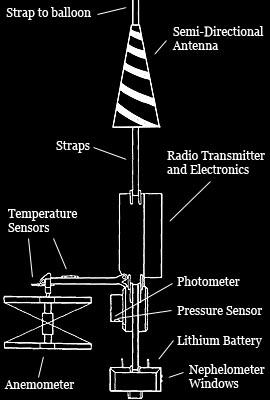

For the Vega mission, V.M. Linkin revived the idea of including balloon-born instruments. The 1.2 meter instrument gondola contained a 4.5 watt radio transmitter with stabilized oscillator, a pressure sensor, temperature sensors, a propeller anemometer, a 400-1100 nm light detector, and a backscatter nephelometer to measure cloud particle density. 16 lithium cells held a 300 watt-hour energy supply. The conical antenna radiated in a funnel-shaped pattern, with a maximum at 167°. The lowest dark red unit seen in the center photo is the deployment control, and was dropped along with the ballast when balloon filling was completed. The gondola was 6.87 kg, and the entire aerostat weighed 21 kg. The 3.4 meter diameter balloon had to withstand the corrosive effects of concentrated sulphuric acid in the clouds, and it also had to survive for months in space, folded up and exposed to vacuum. By now highly experienced in this type of materials problem, Lavochkin engineers fabricated balloons from Ftorlon (a form of teflon) cloth and film. The tether rope and straps between gondola compartments were made from Kapron (a form of nylon-6). The tether used at Venus was 13 meters, much longer than the one seen in the photo above right.

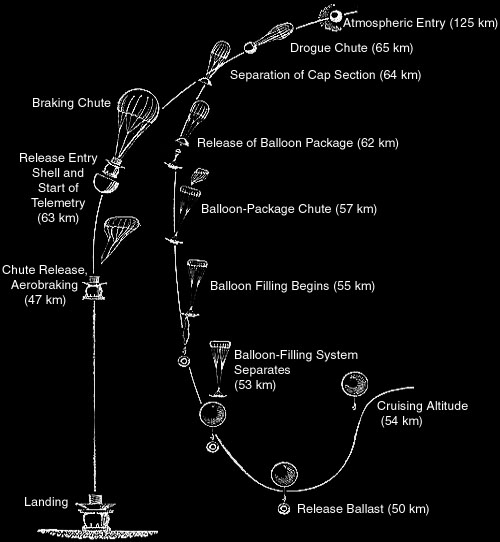

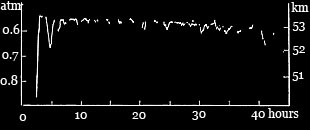

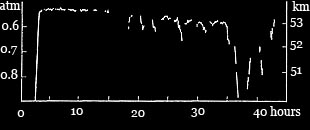

Deployment of Vega Lander and Aerostat The aerostat was stowed in a toroidal compartment fastened to the cap section of the spherical reentry vehicle, fitting around the lander's helical antenna. This included spherical bottles of compressed helium, and a 35 square-meter parachute used during the filling of the balloon. Deployment, diagrammed above, had to be planned carefully and controlled by barometric sensors. If the balloon was filled too early or too quickly, it would burst in the low pressure of high altitudes. If it was filled to slowly, the assembly would drift too far down and be destroyed by high temperatures. The aerostats were deployed at the anti-solar point of Venus, above the continent of Aphrodite Terra. During 46 hours of operation, they traveled about 1/3 of the way around the planet in the 240 km/hour zonal winds. The Vega-1 balloon drifted 7° to the north of the equator, Vega-2 about 6° south. Floating at a mean altitude of 53 km, the balloons were in the middle cloud layer, at an average pressure of about 0.5 atmospheres Signals stopped when batteries were exhausted, and it is not known how much longer the balloons survived.

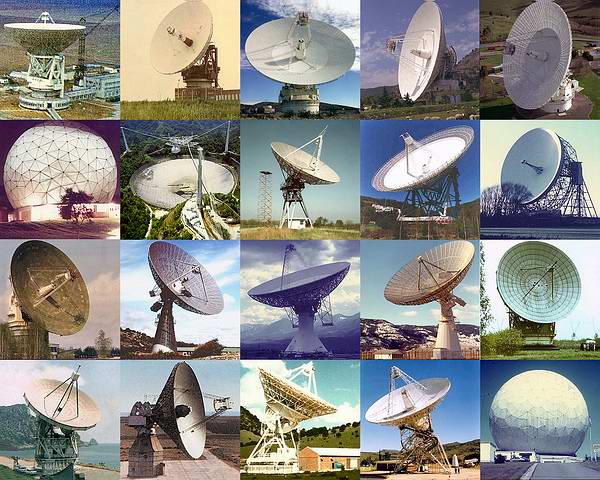

Global Network of Aerostat Tracking Stations Telemetry data, at 1 and 4 bits/sec, was transmitted on an 18 cm band, directly to high gain receivers on Earth. As on previous Venera missions, Kerzhanovich had included stabilized oscillators for Doppler tracking, giving velocity and distance information along the Earth/Venus line. Lateral motion was measured by interferometry, combining radio wave phase information from several Earth stations at once. A carrier wave from the main Vega spacecraft was simultaneously recorded, allowing a very precise measurement of the relative distance between the two transmitters. This differential interferometry technique, developed by NASA during the Apollo program, allowed measurements of velocity within 1 meter/sec and position within 15 km. Aerostat telemetry was convolution coded (K=7, R=1/2) for error correction, then Manchester encoded and phase modulated on the carrier. It is not known if the main spacecraft bus used this sophisticated encoding scheme, for its much more powerful transmissions. It returned data from its parabolic antenna at rates of 64 kilobits/sec, during the Venus and Halley encounters. During spaceflight, the craft was not oriented for high-gain transmission, and all telemetry was sent over the conical semi-directional antennas at 3072 bits/sec. 20 tracking stations were used, including the American and Soviet deep space networks. Seen above: Row 1: Evpatoriia, Ussuriisk, Goldstone, Madrid, Canberra, Row 2: Itapeting Brazil, Arecibo, North Liberty Iowa, Effelsburg Germany, Jodrell Bank Observatory, Row 3: Bear Lakes Moscow, Onsala Sweden, Owens Valley Observatory, Penticton Canada, Pushchino Observatory, Row 4: Simeiz Crimea, Ulan-Ude Siberia, Forth Davis Texas, Hartebeesthoek SA, MIT Haystack Observatory

More turbulence and convention than expected were found in the middle cloud layer, with kilometer-deep excursions of the aerostat at times. Shortly after passing into daylight, the Vega-2 aerostat plunged several kilometers, to a level of 0.9 atmospheres, dangerously close to the lower limit of its stable float zone. After the end of signal, the balloons probably overheated and burst, somewhere on the daylight side of Venus. During the night-time portion of the journey, considerable variations in light levels were detected by the photometer, possibly due to thin spots in the lower cloud layer, revealing the thermal glow of the planet's surface. In addition to sampling light levels, flashes of light were counted by the photometer electronics, but no strong evidence of lightning was found. The Encounter with Halley's CometAfter their missions to Venus, the Vega spacecrafts reached Halley's comet nine months later. Vega-1 passed within 8890 km of the comet nucleus on June 11, 1986, and Vega-2 came within 8030 km on June 15.A total of five spacecrafts encountered the famous comet. From Japan, the Sakigake probe carried 3 experiments and Suisei carried two including a UV camera. From Europe, Giotto carried 11 experiments, including a color television camera. From the Soviet Union, Vega-1 and Vega-2 each carried 14 comet experiments, including their television systems.

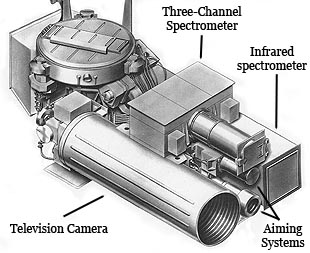

A steerable platform carried a system of television cameras and spectrometers. The narrow angle CCD camera could image visible, red, near and far infrared, and employed automatic aiming mechanisms to track the comet's nucleus. Images revealed an extremely dark (4% albedo) potato-shaped nucleus, emitting at least five jets of dust and gas on its sunward side. A cryogenically cooled far-infrared spectrometer analyzed the range of 2500 - 12,000 nm, while a three channel spectrometer looked at the near infrared (950-1900 nm), visible/UV (275-715 nm) and far ultraviolet (120-290 nm). Vega-1 and 2 flew directly through the tail of the comet, with aluminum shields installed on one side to protect it from the 80 km/sec impacts of minute grains of matter. Both spacecrafts survived, although damage reduced solar-panel power by 50%. Five sensors analyzed the neutral gas, plasma and associated radio-frequency oscillations and magnetic fields around the comet. Six experiments studied the distribution of dust particle size, mass and chemical composition. Results from mass spectrometry showed similarity to carbonaceous chondrite meteors, believed to represent the primordial material of the solar system. After circling the Sun, the spacecrafts passed through the trail of Halley's comet a second time in early 1987, and returned additional scientific information.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Alexander Bazilevsky, Viktor Kerzhanovich, Vladimir Krasnopolsky and Vladimir Kurt for sharing their experiences with the Vega missions. |

The Vega Spacecraft (Front)

The Vega Spacecraft (Front)

(Back)

(Back)

Vega Lander

Vega Lander

Vega Lander

Vega Lander

ISAV-S Ultraviolet Spectrometer

ISAV-S Ultraviolet Spectrometer

MALAKHIT Mass Spectrometer

MALAKHIT Mass Spectrometer

SIGMA-3

SIGMA-3

Temperature/Pressure Unit

Temperature/Pressure Unit

ISAV-A Aerosol Analyzer

ISAV-A Aerosol Analyzer

Soil Drill and Motor

Soil Drill and Motor

Gamma-Ray Spectrometer and Electronics Unit

Gamma-Ray Spectrometer and Electronics Unit

Schematic

Schematic

The Vega Aerostat

The Vega Aerostat

Testing at Lavochkin

Testing at Lavochkin

Aerostat-1 Pressure Readings

Aerostat-1 Pressure Readings

Aerostat-2 Pressure Readings

Aerostat-2 Pressure Readings

Vega Camera/Spectrometer Platform

Vega Camera/Spectrometer Platform

Vega-2 Image of Halley's Comet

Vega-2 Image of Halley's Comet

V.V. Kerzhanovich

V.V. Kerzhanovich

V.M. Linkin

V.M. Linkin

L.M. Mukhin

L.M. Mukhin